HAFNIUM-Linked Hacker Xu Zewei: Riding the Tides of China’s Cyber Ecosystem

How one man’s career reveals the interconnected web of China’s state security apparatus, cybersecurity firms, and strategic industries

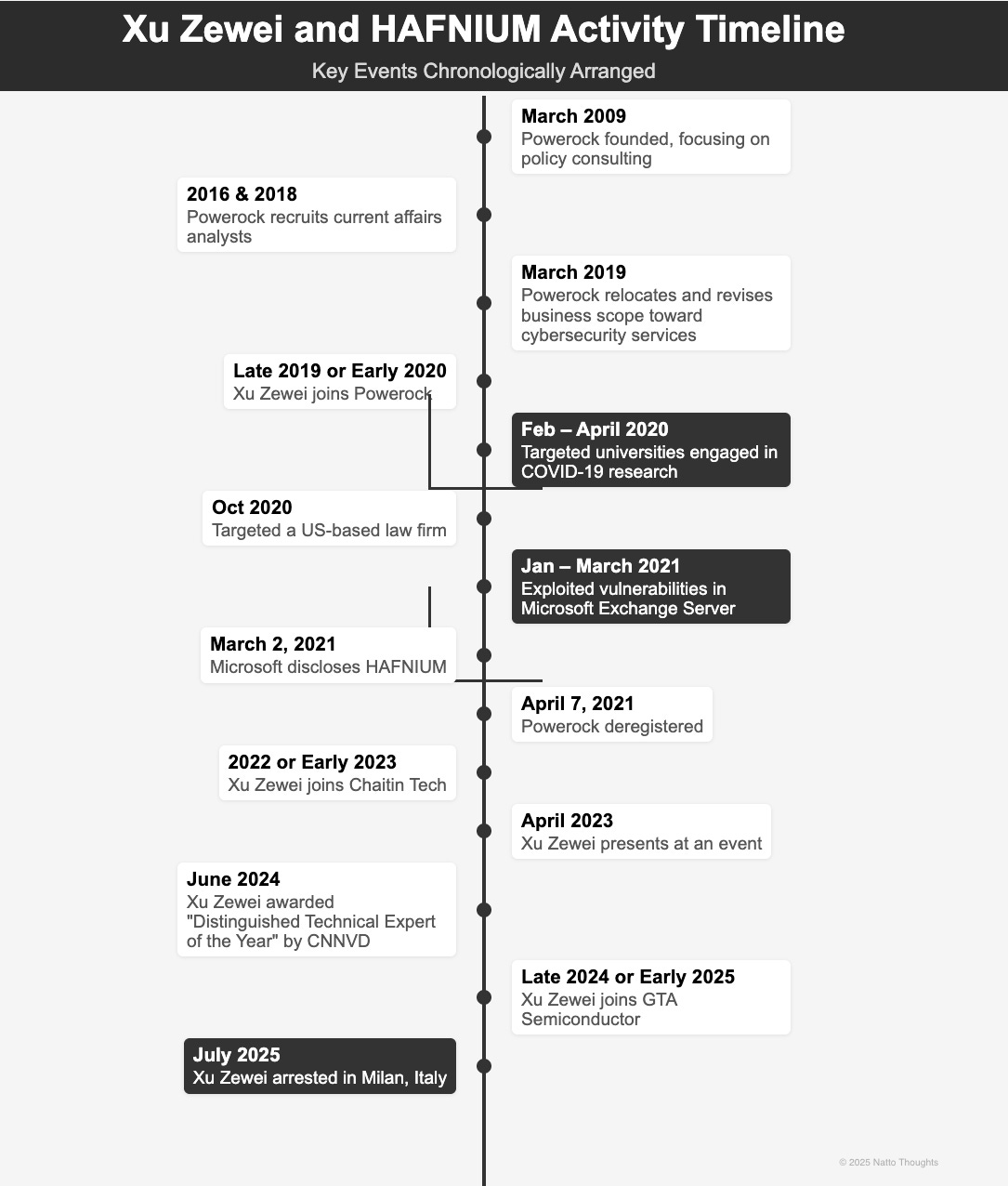

On July 3, 2025, at Milan Malpensa Airport, Italian police arrested Xu Zewei (徐泽伟), whom U.S. authorities allege to be a hacker contracted by the Chinese state. Following the news about Xu’s arrest from Italian media, on July 8, the U.S. Department of Justice (US DoJ) issued a press release and unsealed an indictment, accusing Xu Zewei and his co-defendant Zhang Yu (张宇) of participating in hacking activities between February 2020 and June 2021. These activities were reportedly linked to the Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group HAFNIUM (also known as Silk Typhoon or APT27), involving the theft of COVID-19 research from universities, exploitation of Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities, and compromising thousands of computers worldwide, including those in the United States. As of this writing, Xu remains in custody near Milan and is undergoing extradition proceedings to the United States. During his initial court appearance, Xu asserted that he “has nothing to do with the case,” while Xu’s lawyer stated that “Xu is a victim of mistaken identity, his surname is common in China, and his mobile phone was stolen in 2020.” It was further argued that Xu is a technician employed by (Shanghai) GTA Semiconductor Co. Ltd., on holiday in Italy with his wife.

For Xu Zewei and his wife, their visit to Milan—a dream vacation—took an unexpected turn with the arrest. The circumstances surrounding Xu’s detention have prompted several questions: Is this Xu Zewei the individual sought by authorities? Could he be a victim of identity theft, as contended by his legal counsel? Which companies has Xu worked for? Xu claims employment with Shanghai GTA Semiconductor Co. Ltd (GTA) (上海积塔半导体), whereas the US DoJ asserts Xu worked for Shanghai Powerock Network Co. Ltd. (Powerock) (上海势岩网络科技发展有限公司). Further complicating the situation, findings by the Natto Team and others indicate that between 2022 and at least mid-2024, Xu served as director of security technology at Chaitin Tech (长亭科技), a Chinese cybersecurity firm established by members of Tsinghua University’s Blue Lotus CTF team. As the Natto Team has reported previously, Chaitin Tech is recognized for its top scanning products and vulnerability research capabilities and acts as a technical support unit for both the China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD) and the China National Vulnerability Database (CNVD).

This post aims to clarify the ambiguities surrounding Xu’s professional affiliations, which illustrate the interconnected nature of China’s cyber ecosystem, where talent may simultaneously pursue personal, business, and state interests. Meanwhile, the evolving operational methods of the Chinese Ministry of State Security are also noteworthy.

From the Indictment: Xu Zewei and Shanghai Powerock Network Co. Ltd.

According to the indictment of Xu Zewei and Zhang Yu, the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) alleges that Xu and Zhang acted under the direction of the Shanghai State Security Bureau (SSSB), a regional branch of the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS). They are accused of conducting cyber operations, including exploiting vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server and executing intrusions into thousands of computers globally, purportedly for the benefit of Chinese entities and the strategic interests of the Chinese government.

Xu is described as a contractor for the SSSB and served as general manager at Shanghai Powerock Network Co. Ltd. (Powerock) (上海势岩网络科技发展有限公司). The SSSB reportedly assigned tasks to Xu, who then oversaw hacking activities carried out by other Powerock personnel in support of these assignments and coordinated efforts with fellow hacker Zhang Yu. Following completion of these activities, Xu allegedly reported the outcomes directly to the SSSB. The DoJ further states that “Powerock was one of many ‘enabling’ companies in the PRC that conducted hacking for the PRC government.”

How did Powerock enable the state’s hacking activity?

Research by the Natto Team indicates that Powerock functioned similarly to a front company for the SSSB. The SSSB have likely managed Powerock’s operations through targeted recruitment—especially from local university graduates—as well as direct assignment of responsibilities, a closed feedback mechanism, and a structured reporting process.

Powerock’s Role as a Front Company for the SSSB

Founded in Shanghai on March 16, 2009, Powerock got its start at least one year earlier than front companies linked to the various local state security bureaus of China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) which the US DoJ indictments have identified previously. The company emerged during the timeframe when China’s cybersecurity industry was in its early developing period. The MSS likely had few companies from the cybersecurity industry to choose and work with. At that time, the MSS might have seen the need to create front companies as a means of identifying talent and having direct control over cyber operations.

Chinese business registration records show that Zhang Yu served as a Board Supervisor (监事) at Powerock. (Note: the DoJ indictment named Zhang as a director of Shanghai Firetech Information Science and Technology Ltd, but did not note his position at Powerock). This suggests that Xu, as general manager, operated under Zhang’s oversight. According to the indictment, Xu and Zhang collaborated closely: they discussed potential targets, specific Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) Xu planned to use, research into Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities, and Microsoft’s public report on those vulnerabilities. Their communications indicate that Xu regularly conferred with Zhang, especially during the reconnaissance and weaponization phases of their campaigns.

The SSSB appeared to guide the scope of these operations, providing details such as mailbox usernames or contents related to COVID-19 research, and expecting comprehensive reporting of operational results.

HAFNIUM, the threat group to which Xu has been linked, may have been active far longer than previously believed. While researchers estimated after Microsoft’s 2021 disclosure of the Exchange Server attacks that HAFNIUM had operated since January 2021, the indictment revealed Xu and Zhang’s hacking activities targeting COVID-19 research began as early as February 2020. The Natto Team’s research suggests HAFNIUM’s roots could reach back even further, coinciding with Powerock’s own founding in 2009. Notably, in both 2016 and 2018, Powerock recruited interns and graduates from Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) (上海外国语大学), prioritizing backgrounds in current affairs—aligning with HAFNIUM’s cyber espionage objectives.

A recruitment ad from Powerock at SISU in 2018 described the company as focused on policy consulting and think tank-style research, offering project support, international political briefings, foreign public opinion analysis, and big data services to government agencies, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), and others. At the time, Powerock was seeking a “current affairs analyst.” The role entailed researching the context of news reports, analyzing current trends, processing project data, translating and organizing information, conducting public opinion research, and writing reports. Applicants needed at least a bachelor’s degree in international politics, international relations, English, journalism, or related fields, proficiency in English reading and translation, and experience with relevant research topics.

Powerock Adjusts Business Scope to Align with SSSB’s Cyber Operations

As a front company managed by the SSSB, Powerock strategically altered its business scope to accommodate the requirements of the SSSB's cyber operations. According to Chinese business registration records, Powerock relocated its office and shifted its focus from policy consulting to cybersecurity services in March 2019. The revised business scope encompassed intrusion prevention technology and abnormal traffic analysis, operating system and application security and vulnerability identification, as well as virus prevention technology research. These modifications were likely accompanied by the recruitment of cybersecurity professionals with expertise in both defensive and offensive cyber capabilities, particularly in vulnerability research and discovery. The Natto Team assesses that Xu Zewei was likely brought on by the SSSB during this period, enabling the SSSB to assign Xu to lead targeted campaigns from early 2020 through mid-2021.

Powerock Deregistered after Microsoft Publicly Disclosed HAFNIUM

As previously discussed, the indictment of Xu and Zhang revealed that on March 3, 2021—the day after Microsoft published its report on “HAFNIUM targeting Exchange Servers with 0-day exploits”—Xu and Zhang discussed both the vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server and the release of the corresponding security patch. It is likely that, on this day, Xu and Zhang realized their threat campaigns had been exposed and reported this development back to the SSSB. Just a month later, on April 7, 2021, Powerock deregistered its business. This appears to be a standard intelligence operation procedure to prevent further exposure of the SSSB’s intelligence assets.

Interestingly, when the Natto Team asked Chinese search engine Baidu’s AI Chat in Chinese, “Why did Powerock deregister?”, DeepSeek-R1—a tool from Chinese AI startup DeepSeek—offered one possible explanation: “Around 2021, the Shanghai municipal government focused on cleaning up ‘zombie enterprises,’ which are companies with no actual operations and abnormal tax status, requiring their mandatory deregistration. If Powerock resembled a ‘zombie enterprise,’ it could have fallen within the scope of this directive.” Indeed, a front company like Powerock shares many characteristics with such “zombie enterprises,” but the Natto Team did not expect DeepSeek-R1 to so clearly recognize this resemblance.

Did the deregistration of Powerock mean that Xu Zewei was out of his position as general manager? Yes, that appears to have been the case.

Drawing from Open-source Information: Xu Zewei and Chaitin Tech

After Powerock was shut down in April 2021, Xu Zewei appears to have secured a new role with Chaitin Tech, one of China’s most prominent cybersecurity firms. Renowned for its expertise in vulnerability research and prowess in both attack and defense, Chaitin Tech is often described within the industry as “a defense team that knows the offense best.” It is likely that Xu’s experience at Powerock helped him land a position as chief security researcher around 2022 or early 2023.

The Natto Team found evidence of Xu’s public involvement in April 2023, when he appeared at a network security attack and defense technical exchange conference as Chaitin Tech’s chief security researcher, presenting on advanced network attack techniques. Later, on June 20, 2024, at the China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD)’s 2023 Annual Work Review and Outstanding Recognition Conference, Xu—by then the director of security technology at Chaitin Tech—was awarded the “Distinguished Technical Expert of the Year Award.” The shift in Xu’s title suggests he was promoted from chief security researcher to director of security technology within about a year.

Xu’s career at Chaitin Tech appeared to be on a strong upward trajectory. However, it seems he believed he could achieve even greater success elsewhere.

In Their Own Words: Xu Zewei and GTA Semiconductor

Xu changed jobs again around late 2024 or early 2025. After his arrest, Xu’s spouse informed the Italian police that Xu was working as an IT manager at Shanghai GTA Semiconductor Ltd (GTA), developing IT systems and network infrastructure. This new role at GTA provided some Chinese-language media with grounds for criticizing Xu’s arrest as part of “the US containment of China’s scientific and technological development,” given the strategic importance of the semiconductor industry and GTA’s leading role in automotive electronic chips. According to the company’s website, GTA specializes in manufacturing automotive-grade chips and holds 80 percent of China’s domestic market for IGBT (insulated-gate bipolar transistor) chips used in new energy vehicles. Major Chinese electric vehicle makers, including BYD, are among GTA’s clients.

Various Chinese commercial internet media platforms, such as sohu.com and ifeng.com, as well as social media posts, reported on Xu’s arrest. Many of these posts appeared to be generated by artificial intelligence (AI) tools. The predominant narratives included allegations that the US had not provided sufficient evidence to support its hacking accusations against Xu, arguments that China had no reason to steal COVID-19 research since it was ahead of the US in that field, and claims that Xu’s work at GTA Semiconductor—focused on automotive electronic chips—was unrelated to COVID-19 research. These narratives also criticized the US for its “long-standing policy of long-arm jurisdiction” and suggested the true intent was to contain China’s technological progress. Many commentators compared Xu’s case to Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou’s extradition, dubbing it “Meng Wanzhou 2.0.”

In contrast, the Chinese government and official Chinese media have largely remained silent on Xu’s arrest, apart from the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson’s standard remarks—reiterating China’s opposition to the use of so-called cyber issues to maliciously smear the country.

What’s Next?

As of this writing, three weeks after Xu’s arrest, the extradition process appears far from straightforward. The FBI’s Houston field office posted on the social media platform X that Xu Zewei is “one of the first hackers linked to Chinese Intelligence services to be captured by the FBI.” (Most US indictments against foreign intelligence-linked hackers have been in absentia). Media reports have hailed Xu’s arrest as a significant breakthrough for the FBI. However, his case reminds the Natto Team of the earlier case involving Chinese malware developer Yu Pingan, also known as “Goldsun.”

The FBI arrested Yu Pingan on August 21, 2017, at Los Angeles International Airport when he entered the US for a conference. On the same day, a complaint against Yu was filed and unsealed the next day, August 22, 2017. The US Department of Justice accused Yu of conspiring with two other Chinese nationals to hack into at least five US companies between 2011 and 2014. Although the complaint did not directly tie Yu to the 2015 data theft from the US Office of Personnel Management and insurance company Anthem, malware tools he created and used—including one known as “Sakula”—were used in those hacks.

After spending 18 months in a San Diego federal detention center, Yu pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit computer hacking. In February 2019, a federal judge sentenced Yu to time served, allowing him to return to China.

In November 2019, a Reuters reporter based in Shanghai found Yu Pingan teaching at Shanghai Commercial School, a state-run vocational technical high school where he had taught prior to his arrest in the US. Yu was teaching two basic computer courses, including one on internet security.

Could a scenario similar to Yu Pingan’s—being caught, released, and then returning to his previous job—play out for Xu Zewei? Even though the first hurdle is to bring him to US soil, only time will tell.