Intrusion Truth Methods: How Can They Get It Right Again and Again?

Who are the mysterious hacker whisperers Intrusion Truth? What kinds of tradecraft have they used? What can cyber threat analysts learn from them?

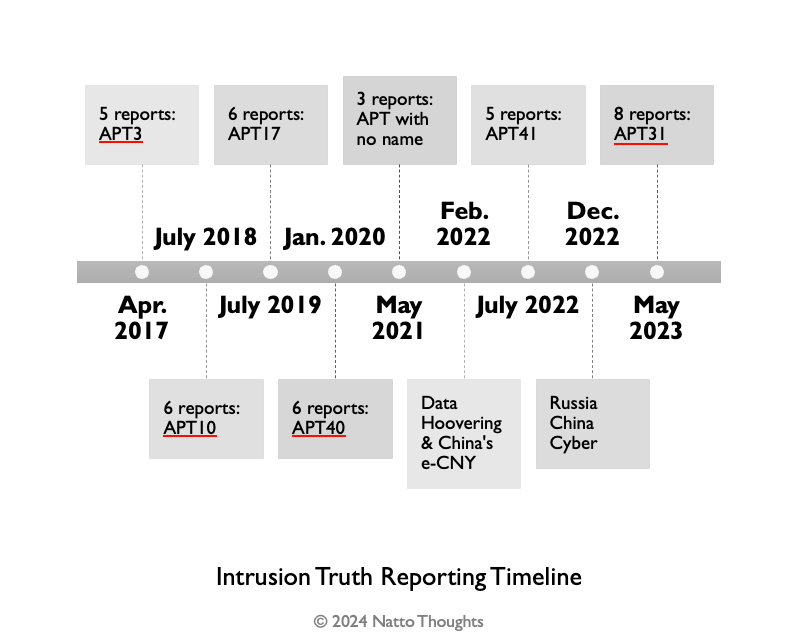

In late March 2024 the United States Department of Justice (US DoJ) unsealed an indictment alleging that seven Chinese hackers operated as part of Advanced Persistent Threat (APT)31 group “in support of China’s Ministry of State Security’s transnational repression, economic espionage and foreign intelligence objectives.” At the same time, the US Department of the Treasury imposed sanctions on APT31-affiliated company Wuhan Xiaoruizhi Science and Technology Company (武汉晓睿智科技有限公司) (Wuhan XRZ) and on two of the seven hackers. Many of us who follow the whereabouts of Chinese threat actors had an aha moment; we recalled that Intrusion Truth, an anonymous group that hosts a blog unmasking the real identities of Chinese threat actors, identified some of those hackers and WuhanXRZ back in May 2023. Wow, Intrusion Truth was right (again)! Since its first post in April 2017, Intrusion Truth has revealed actors and companies associated with four Chinese APT groups – APT3, APT10, APT40, and most recently APT31 – that were followed by indictments from the US DoJ.

Who is Intrusion Truth? How Could Intrusion Truth repeatedly get it right? What kinds of tradecraft has Intrusion Truth used? What can cyber threat analysts learn from them? Let’s start from the beginning.

Getting to Know Intrusion Truth

First appearing on April 18, 2017, an anonymous group calling itself Intrusion Truth started hosting a WordPress blog and a Twitter (now known as X) account in which they reveal what they say are real-world identities of Chinese threat actors who have links to the Chinese Ministry of State Security. In their first interview via email with Motherboard in August 2018, Intrusion Truth indicated that their anonymity enables them “to contest China’s despicable activities in Cyberspace.” In the interview, Intrusion Truth stressed that it was not important what color – a red or blue force – they were [in the cybersecurity field, “red teams” probe a client’s defenses to find weak spots, while “blue teams” help them defend]. Nor did it matter whether they wore black or white hats [referring to criminal hackers and researchers, respectively], or if they were “‘Black Knights’ who had to paint their armour with dark paint to mask their affiliation and protect their identities.” Their efforts were “to identify the individuals, companies and state institutions behind the damaging attacks that hit the West” and to uncover Chinese threat groups “stealing our intellectual property.” It appears Intrusion Truth has gone into battle with China to protect “the West.”

Five years later in 2022, in another email interview with American investigative journalist Kim Zetter, Intrusion Truth emphasized again their “primary goal is to expose the whole truth of Chinese state-sponsored hacking,” saying they “can’t let state-sponsored Chinese hackers act with impunity.” And indeed, their revelations align with subsequent law enforcement actions: the US DoJ has indicted threat actors identified by four of the five known APT groups about whom Intrusion Truth has reported. (Actors affiliated with the fifth group, APT17, whom Intrusion Truth identified in 2019, have not been indicted as of this writing). Although the suspects remain in China and the allegations will never likely be tested in a US courtroom, the naming and shaming likely constrains their actions.

Other than identifying threat actors associated with known threat groups, Intrusion Truth also added value to US DoJ’s investigation of Chinese threat actors by discovering their networks and identifying more actors. For example, Intrusion Truth’s 2021 investigations into an ”APT with no name” and their 2022 report on APT41 were based on threat actors disclosed in previous US DoJ indictments. Lastly, in 2022 Intrusion Truth touched on a couple of current issues and published two reports, one about the risks of China’s e-CNY e-currency to attendees of the 2022 Winter Olympics and the other about China’s state hackers’ intelligence collection on Ukraine and Russia. These two reports were different from their routine reporting.

Intrusion Truth has published relatively few threat investigations in the past seven years, averaging only about one case per year. (See chart below)

However, because 80 percent of their reports so far have led to a US DoJ indictment, Intrusion Truth has built a reputation and a loyal follower base that anxiously waits for any new posts to drop.

Intrusion Truth Methods

After publishing investigative reports about APT3 and APT10 in 2017 and 2018, respectively, a 2019 Intrusion Truth report outlined a pattern behind the Chinese Ministry of State Security’s cyber operations. The pattern looked like this: “a regional office of the MSS (Ministry of State Security) creates a company, hires a team of hackers and attacks Western targets.” Subsequently, Intrusion Truth tested the pattern with their APT17 investigation in 2019 and their APT40 investigation in 2020, which they saw as vindicating their assessment.

The Natto Team notes that this is correct as far as it goes. However, the i-SOON leaks confirm Natto Team’s previous assessments that the pattern is more nuanced. The MSS not only creates companies that are purely front companies, but also works with existing companies, such as i-SOON that are real businesses. The US indictment of APT31 agrees with this, alleging that Wuhan XRZ was a front company but that the MSS suspects also worked with another company, Wuhan Liuhe Tiangong Science & Technology Co., Ltd (武汉六合天工科技有限公司). Future Natto Thoughts postings will discuss further the difference between front companies and real companies.

Nevertheless, given Intrusion Truth’s prescience in identifying Chinese threat actors, their techniques deserve emulation. How have Intrusion Truth done their investigations? To answer this question, let’s first see where Intrusion Truth start their investigations.

Starting Points

A review of Intrusion Truth’s reports shows at least four starting points:

● Starting from other researchers’ APT reports: Intrusion Truth started by looking into previously published threat intelligence reports, including reports from companies and organizations such as FireEye (now Trellix), PriceWaterhouseCoopers, Novetta, Symantec, BAE Systems, and the Japan Computer Emergency Response Team (JPCERT), for clues in their early reports about APT3 and APT10. ( https://www.jpcert.or.jp/english/) For example, Intrusion Truth investigated domains that FireEye had identified as communicating with APT3’s Pirpi backdoor. By digging into the domain information, Intrusion Truth located Wu Yingzhuo, a threat actor associated with APT3.

● Starting from a tip. Intrusion Truth started investigations from “tips” which a “collaborator” or “the community” or “a friend” or “cyber threat intelligence analysts” gave to them. Intrusion Truth emphasized the importance of “The Intrusion Truth community” providing leads for any given investigation. In some cases, those tips may be out of reach for ordinary threat analysts in the West. For example, in the APT17 investigation, Intrusion Truth started with a tip from a source who said that Guo Lin (郭林), an MSS officer in Jinan city, Shandong province, was involved in cyber operations. Guo Lin is a very common name in Chinese language, like John Smith in English; there may be hundreds of people named Guo Lin. Narrowing the Guo Lins down to the the MSS officer was not an easy job. It is not clear how, but Intrusion Truth pinpointed a Guo Lin who wrote an academic paper called “Method of Classifying Attacks based on Multi-dimension” as a Masters student and noticed Guo Lin’s email address. Through that address, Intrusion Truth discovered Guo Lin’s link with MSS. In addition, the tip itself had to be from people in the field and with local connections to the job responsibility of a particular MSS officer.

● Starting from searching science and technology companies in a region. In the investigation of APT40, Intrusion Truth started by searching science and technology companies in Hainan province. China has 23 provinces, 5 autonomous regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang, and 4 municipalities. That Intrusion Truth chose Hainan province to start this investigation probably was not a random choice. Intrusion Truth explained that they looked into Hainan province, a semi-tropical island located in Southern China, because “Northern China has received much, presumably unwelcome, attention from this blog already.” However, Hainan province has over one thousand science and technology (S&T) companies. Researching over one thousand S&T companies is daunting, but Intrusion Truth narrowed down to search S&T companies which had also posted job ads for penetration testers.

● Starting from indictments. In 2021 and 2022, Intrusion Truth’s investigations focused on expanding knowledge of US DoJ-identified Chinese threat actors to disclose more actors and companies related to threat groups. For example, Intrusion Truth’s May 2021 “APT with no name” investigation put a name on the person that the DOJ’s Li Xiaoyu and Dong Jiazhi indictment had identified as “MSS officer 1.” In the investigation of APT41, Intrusion Truth dived deep into the network of APT41 and discovered other actors and companies affiliated with APT41.

Tools and Resources Used

Conducting cyber threat intelligence (CTI) investigations, Intrusion Truth has used tools and resources which CTI analysts commonly use, such as DNS search, IP address history, and social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and Facebook. Intrusion Truth also heavily leverages the Chinese Internet. As we know, China has its unique Internet ecosystem since most of the Western social media platforms are blocked in China. Intrusion Truth has used all possible sources of the Chinese Internet, from Chinese social media platforms such as QQ, to recruitment sites such as zhaopin.com, to Chinese university job sites, business information databases and academic journals. Lastly, Intrusion Truth relies on dark web and Chinese hacker forums to further their investigation. For example, in the APT31 investigation, Intrusion Truth discovered a data set for sale on the dark web that exposed two MSS officers who managed APT31-affiliated company Wuhan Xiaoruizhi Science and Technology Company.

Intrusion Truth also used tools that may be controversial or have legal issues for regular threat intelligence practices. Journalists, threat intelligence researchers and government employees may have their own understanding of the ethics and legalities of accessing information that has been disclosed without authorization. In several occasions, Intrusion Truth used the “social engineering database”(社工库), a stolen database, to access threat actors’ social media accounts.

Intrusion Truth might have used offensive hacking, hired a third party to do the dirty work, or used insider access to get information so they could complete threat actor attribution. In the APT10 investigation, Intrusion Truth obtained an Uber (ride sharing app) receipt that made the connection to one of the APT10 actors working for the state security. In another case, Intrusion Truth used a Bank of China credit card statement to identify an intelligence officer working with two US DoJ-indicted Chinese threat actor suspects. Intrusion Truth also used leaked or stolen Chinese government social insurance information to find employers of threat actors and information from a likely stolen personal cloud storage account to confirm their findings. Intrusion Truth often mentioned information coming from “collaborators” or “the community” or “a friend” or “cyber threat intelligence analysts,” but did not elaborate.

Intrusion Truth might have on-the-ground operations, such as connections in China who could help them to access certain information only available in China, such as a printout they cited in their APT17 investigation. In the APT31 investigation, “a friend” of Intrusion Truth went to a company location and snapped a couple of pictures for their investigation.

Lastly, as previously mentioned, Intrusion Truth relied on “the Intrusion Truth community” and on the broader information security community to provide leads for investigations. Crowdsourcing and asking for help were important to ensuring success for their investigations. This also means the analysts of Intrusion Truth, to a certain degree, were well connected with the information security community, possibly including elements of that community who operate covertly.

Lessons CTI Analysts can Learn from Intrusion Truth

Intrusion Truth wowed many CTI researchers and analysts, including the Natto Team , with their achievement of identifying networks of Chinese threat actors behind the APT keyboard. Intrusion Truth’s investigations have deepened our understanding of the Chinese cyber threat landscape. What can we learn from their methods?

● A research or investigation may not just end after the research is published or the investigation is completed.

The fact that Intrusion Truth started a few of their investigations by digging into research reports published several years ago shows the value of seemingly outdated research. Many cyber threat intelligence analysts are often busy chasing the next threat actor or moving from one investigation to the other; they may not often go back to their previous published reports and reexamine those research findings. In a way, Intrusion Truth extended the value of those “outdated” reports and dug for treasure. (For a Russia-related example of this, see here.)

● Building a community is important for threat hunting.

Intrusion Truth mentioned many times that help from the Intrusion Truth community enabled their investigations. The importance of building a community should also apply to the broader InfoSec community. Threat hunting is like assembling a 1000-piece jigsaw puzzle. Exchanging research ideas, information and approaches among a trusted community can help put those pieces together efficiently. Of course, exclusive “tips” may be even better at helping find gold.

● Understanding a threat environment makes threat research go deeper. Intrusion Truth’s success at identifying Chinese threat actors built upon a great deal of knowledge of Chinese threat actors’ operating environment. Comprehension of the Chinese language, familiarity with the Chinese Internet, and close following of geopolitical situations in the region have made the results of Intrusion Truth’s investigation possible. The Natto Team aspires to bring the same deep language and country knowledge to its analyses of China and the former Soviet countries.

Intrusion Truth methods may not apply to every CTI researcher, but their methods are very inspiring. As mentioned above, the Natto Team would like to generate more Natto Thoughts to question some of the truths told by Intrusion Truth, such as: were some of those front companies they mentioned just front companies or were they real businesses? Stay tuned.

In case You Find it Helpful: Investigation Resources Mentioned in Intrusion Truth Reports

Chinese social media platforms: Weibo, Tencent Weibo, Fanfou (the first Twitter clone), Renren (Facebook clone); Qzone QQ; QQ

Chinese recruitment sites: zhaopin.com; leipin.com, yingjiesheng.com (a job-hunting website for college and school students); 51job.com (51job)

Chinese university job sites: Hainan University; Sichuan University; yjbys.com

Chinese online classified advertising sites: ganji.com; huangyeso.com

Chinese business registration information sites: Tianyancha(天眼查); xizhi.com (悉知)

Chinese business tax information: qixin.com (启信宝)

Chinese hacker forums and blogs: Pediy[.]com看雪论坛; binvul[.]com; blog.csdn[.]net; 20cn[.]org; www.e365[.]com

Chinese academic journals: Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI)

Chinese public service maps: public toilet information