Putin: The Spy as Hero

What a Fictional Soviet Secret Agent Can Tell Us About Russian Psychological Operations

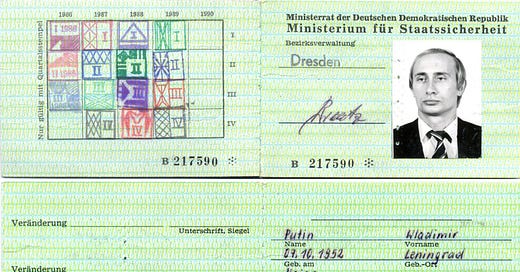

Note added July 31 2024: This was our very first posting, back on April 6, 2023. It analyzed a popular Soviet spy movie that helps explain Vladimir Putin's mind games against a Western world he distrusts. We think it remains relevant today. Subsequent postings fleshed out some of these themes in more detail. For example, further detail on disinformation can be found in the three-part "Disinformation Handbook" beginning here.Vladimir Putin’s identification card from the East German State Security Ministry (Stasi). Source: Wikimedia Commons.

If you grew up in the former Soviet Union, chances are you encountered a favorite holiday tradition, which continues in Russia to this day: watching the 1973 spy movie “Seventeen Moments of Spring.” Based on a book and TV series from the 1960s-1970s, this story of the fictional Max Otto von Stierlitz, a Soviet spy embedded in the German Nazi hierarchy in the closing months of the Second World War, evokes nostalgia in even the most cynical émigrés. The fictional Stierlitz character has his own Wikipedia page and a living set of jokes about his superhuman abilities.

One big fan of Stierlitz and other on-screen Soviet spies was Vladimir Putin, who would go on to become the president of Russia. Indeed, the worldview of the film and the character of Stierlitz provide a glimpse into Putin’s own worldview and actions. “Seventeen Moments of Spring” and other state-ordered popular cultural productions drew on the Soviet public’s memories of the Soviet Union’s existential struggle against Nazi Germany in World War II. That genuinely popular sentiment continues to provide one of the main sources of legitimacy for Putin’s government and helps explain why Putin has depicted the all-out attack on Ukraine in 2022 as a war against “Nazis.”

The Stierlitz character in the book and film [also spelled Shtirlits, Shtirlitz or Stirlitz] was a model chekist. “Chekist” is a Russian term for an intelligence operative, based on the Russian acronym for the Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage in early Soviet days. Numerous analysts have enumerated how President Putin reflects a “Chekist worldview.” Features of this worldview include a perception of being surrounded by enemies, particularly the United States, against whom any and all means are legitimate; and a preference for operating in secrecy. The ideal chekist is disciplined, sober, courageous, ideologically committed, and honest.

In the “Seventeen Moments” film, the Stierlitz character, embedded within the Nazi hierarchy, must operate alone, skillfully navigating a dangerous environment, and maneuvering among backstabbing colleagues. Stierlitz must prevent the Soviet Union’s allies from carrying out a treacherous separate peace with Germany. Stierlitz thinks on his feet, continually improvising backup plans and telling different stories to different people, in a sort of three-dimensional chess game. A wrong move could lead to torture and death. But Stierlitz’ tough exterior conceals a deep motivating love for his Soviet motherland. He sacrifices his personal life, so deeply embedded in his fictional Nazi identity that he is allowed only one brief glimpse of his own wife, at a distance. Stierlitz is calm, focused, and clever, even in moments of dire danger.

In one scene, after Allied bombing levels the building where his fellow Soviet spy lived, Stierlitz learns that the Gestapo has located the spy’s radio suitcase with fingerprints on it. Thinking quickly, Stierlitz hastens to the official in charge of the suitcase and promises to interrogate the spy himself. Then, before leaving his colleague’s office, he asks to borrow some sleeping pills, implying that that was why he came. Stirlitz reasons that people always remember the last thing you tell them at the end of a conversation (https://www.youtube[.]com/watch?v=G7WtXrI4r5M minutes 31-36:30).

Nevertheless, the Gestapo also finds Stierlitz’ own fingerprints on the spy radio suitcase. The Gestapo chief brings him to a torture chamber and leaves him alone to “remember” an innocent explanation for this. Surrounded by gruesome instruments, Stierlitz finds a box of matches and sits, arranging and rearranging the matches, until he has concocted a plausible alibi (https://www.youtube[.]com/watch?v=kMlPix9jbv0, minutes 0:00-15:00, 25:30-33:00, 50:09-59:00). Stierlitz has the courage and cool head to think under pressure.

Update July 29 2024: Even though it was ostensibly set in Nazi Germany, the film was also a mirror of Soviet society, said Soviet-born German writer Wladimir Kaminer in a 2020 German-language interview. Ordinary people could identify with Stierlitz’ struggle merely to survive in an inhuman system. Like the film’s hero, they had to hide their real selves in public. Only at their kitchen tables could they utter their real thoughts (minutes 8:53-16:14 of the interview).

Putin as Stierlitz

At the end of the chaotic 1990s the Russian population yearned for a leader like the fictional Stierlitz, according to focus groups that former Kremlin spin doctor Gleb Pavlovsky conducted. Tasked with finding a successor to the brash, often-inebriated President Boris Yeltsin, Pavlovsky told the Financial Times that he helped choose Putin as that successor and helped groom Putin’s image as a sober, physically fit and level-headed leader. Putin’s image-making over the years included a 1992 documentary in which Putin even reenacted a scene from the “Seventeen Moments” movie (https://www.youtube[.]com/watch?v=oPFhnGkX7E8&t=142s, minutes 2:05-2:26).

In some ways, Putin’s real biography resembled that of the fictional Stierlitz. Stories of Stierlitz and other heroic Soviet spies formed part of young Vladimir Putin’s reading diet. He was a chekist through-and-through. Born in 1952, he wanted to be a spy by age 16. After college in the 1970s, he went through KGB training and performed counter-intelligence monitoring of foreigners in Leningrad, the second largest city of the Soviet Union. In the late 1980s he served in Dresden, East Germany, observing first-hand the unrest that accompanied the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1991 the KGB brought him back to the second city, newly renamed Saint Petersburg, where in addition to monitoring foreigners, he also handled foreign trade. After a failed hard-line coup attempt in August 1991 augured the end of Communist rule and of KGB preeminence in the Soviet Union, Vladimir Putin officially resigned from the KGB. His Soviet homeland ceased to exist on December 25 1991, in what Putin has famously called a “geopolitical catastrophe” and a “genuine tragedy” for the people of Russia. Putin subsequently held government jobs in Saint Petersburg and then Moscow before becoming head of the KGB’s successor agency, the FSB, in 1998 and president of Russia in 2000.

He appears to see himself as a loner in a dangerous world, forced to use his wits to defeat stronger opponents. Growing up slight of stature in a rough neighborhood, he found protection and belonging in a community of judo practitioners, some of whom reportedly associated with organized crime groups. A formative incident in December 1989, when he was serving as a Soviet KGB liaison in Dresden, East Germany, likely strengthened his sense of isolation. Amid massive demonstrations that followed the fall of the Berlin wall, crowds stormed the headquarters of the Stasi, the German secret police, and the neighboring KGB building. Putin recalled that when his colleagues frantically called for military backup, they heard, “Moscow is silent.” They were on their own. Putin-approved reports differ on whether he himself brandished a pistol, had a nearby soldier cock his weapon, or simply announced that his KGB comrades were armed, but all agree that Putin calmed the crowd with his quick thinking and knowledge of the German language.

Agile and Crafty in a Hostile World

Analysts agree that Putin believes he has a mission to strengthen the Russian state and undo the humiliation Russia suffered with the breakup of the Soviet Union. Perceiving enemies all around, and even putative allies as potentially treacherous--distrust continues to mark Russia’s relationships even with Iran and with China--Putin seeks to exploit any weaknesses of more powerful adversaries. Analysts have drawn on Putin’s martial arts experience to explain his approach; for example, a report by US government-funded news source Radio Free Europe suggested in 2012, “Putin has applied the lessons of judo -- the nimble sidestepping, the stealthy art of using the weight of your opponent against him, the combination of patience and ruthlessness -- to his political career.” Putin keeps open his options, adapts and improvises, lies and manipulates.

Perceived Western Treachery

Putin’s messaging portrays the Western countries as hypocritically talking about democracy but really seeking to maintain world dominance and humiliate Russia. Russian state officials and media frequently portray historical US support for popular movements as the US using strong-arm tactics against sovereign governments. These include the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999 to enforce the secession of Kosovo; US support for so-called “Color Revolutions” in the Republic of Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, and Kyrgyzstan in 2005; the Arab Spring uprisings in 2010-2012; and the fair-elections protests in Russia in 2011-2012 that brought hundreds of thousands of protesters to Moscow streets to denounce Putin and his party as “crooks and thieves.” Putin has claimed that then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton gave the “signal” to the Russian protesters who nearly unseated him.

One such incident confirmed Putin’s perception of the West as treacherous and that he faced mortal danger if he loosened his grip on power. In 2011, the UN Security Council (UNSC) resolved to enforce a no-fly zone over Libya, where dictator Muammar Qaddafi appeared ready to unleash a bloodbath against protesters. Russia’s then-President Dmitriy Medvedev, who at the time was presenting a benign face to Western countries, abstained rather than block the UNSC resolution. This Western “crusade” against Qaddafi--punishing the Libyan leader for domestic human-rights violations even after Qaddafi had voluntarily given up his weapons of mass destruction--horrified Putin. When Qaddafi’s enemies later beat him to death, Putin reportedly feared that he too could face a similar fate if he fell from power. Putin interpreted this incident to mean that regardless of what concessions he made, the West could not be trusted.

Similarly, Putin has portrayed the EuroMaidan protests of 2013-2014 and Revolution of Dignity in Ukraine, the anti-Russian sanctions that followed Russia’s seizure of Ukrainian territory in 2014, and Western support for Ukraine after the all-out Russian invasion of 2022, as evidence of a Western attempt to use Ukrainians to undermine Russia. By 2023, Russian officials and state media were portraying the war against Ukraine as a new “Patriotic War” alongside World War II and the 1812 war against Napoleon. They attempt to portray the current Ukrainian government as fascist. This is ironic, considering that Ukraine’s president is Jewish and that Russia has encouraged neo-Nazi movements worldwide. Nevertheless, Putin’s government has attempted to capitalize on genuinely popular memories of the struggle against Hitler to justify the war against Ukraine and its Western backers.

Superhero Image and Reality

Russian state media has cultivated an image of Putin as the tough, heroic figure on a par with Stierlitz: riding horses barechested, sedating tigers, hang-gliding with birds and discovering ancient pots on the seabed. These images have in turn spawned social media memes mocking this portrayal, similar to Stierlitz jokes.

Putin’s bravado does not quite match that of the fictional hero. As security analyst MarkGaleotti and other analysts have argued, Putin is not an omniscient three-dimensional chess player but is often reactive and opportunistic and relies on often-misleading information that his sycophantic advisors feed him. Rumors periodically crop up that he is out of reach, tired, or sick. Furthermore, Putin’s chekist entourage acts like a kleptocracy. These self-proclaimed guardians of the Russian nation loot Russian taxpayers’ money to fund their own lavish lifestyles, though one prominent study says they are also using the country’s riches for a political purpose—to influence and undermine the West.

Even if he is not the superhuman that Stierlitz is, Putin seemingly tries to emulate the courage and cleverness Stierlitz represents. Like Stierlitz, he has no compunctions lying to all sides, because a war is on.

What Would Stierlitz Do?

Alone amidst mortal enemies and able to rely only on his wits, Stierlitz cleverly told different lies to different people in an effort to divide, mislead and manipulate them. He took advantage of their weaknesses and their short memories to distract and confuse them. Putin’s government also relies on psychological operations, including obfuscation, misdirection and disinformation, to divide, discredit, demoralize and distract his critics, whether inside Russia or in the West.

Against the domestic opposition, over the years Russian intelligence services have carried out distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks on liberal media, hacked oppositionists’ emails and leaked compromising information, set up alternative “civil society” groups to draw support away from opposition activists, and tried to scare the population into thinking that Russia without Putin would disintegrate into war, invasion, and 1990s-style chaos and poverty. They have carried out similar information operations against societies in countries that criticize Russia.

“People Remember the Last Thing You Tell Them”: Soviet-Style Propaganda for the 21st Century

Internationally, Russian intelligence services have updated a long tradition of Soviet “active measures”—a term referring tocovert attempts to influence other countries’ political landscape and decision-making. They have taken full advantage of 21st-century social media to unleash what analysts have called a “firehose of falsehood.”. Most famous for their attempts to undermine Hillary Clinton’s presidential candidacy in 2016, Russian and other foreign actors have continued to spread disinformation to US and other Western audiences, often through proxies such as sympathetic Westerners and often by amplifying divisive messages already present on the Internet. (Disinformation refers to the deliberate spread of false or misleading information, in contrast to “misinformation,” the sometimes-unwitting spread of incorrect information). In 2022, for example, pro-Kremlin networks of inauthentic social media accounts promoted anti-Ukrainian narratives and amplified disinformation about the integrity of US elections ahead of the midterm vote. Russian state-owned propaganda network RT (Russia Today), ironically using the slogan “Question more,” abuses liberal values of open media and free inquiry to discredit science, the professional media, and even the idea of truth. Exploiting deeply held convictions to widen fissures in target societies, they have posed as both feminists and anti-feminists, Black activists and white supremacists, or pro- and anti-vaccine movements; for example, Russian trolls created fictional social media personas that amplified Muslim-Jewish tensions, part of an online “clamor” that helped to fragment the Women’s March movement of 2017.

Rather than always relying on direct orders from President Vladimir Putin, Russian influence operations often resemble throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what will stick. Putin’s speeches and state media set the tone and identify targets, and Putin loyalists compete to attack those targets, allowing Putin to deny direct involvement. This reliance on “entrepreneurs of influence” yields what security analyst Mark Galeotti has dubbed an "adhocracy” of “competing, semi-autonomous actors expected to …generate their own plans to work toward the state’s broad objectives.” Putin plays them off against each other to prevent any one from gaining too much power. A classic analysis by Clifford Gaddy and Barry Ickes portrayed Putin’s system as a “protection racket” that uses complicity and compromising information to prevent Russian business or political elites from threatening Putin’s own power.

Countering Putin’s Mind Games

Putin’s self-image as a clever spy, surrounded by enemies and treachery and reliant on his wits to survive, helps explain Putin’s actions. He is totally cynical about the rhetoric of democracy and even the idea of truth, viewing them as hypocritical. He relies heavily on information operations to take advantage of the fast-paced news cycle and the media appetite for sensation. He counts on the world community’s short memories and distractibility to amplify divisive messages.

Consumers of media and social media can protect themselves from these manipulative efforts, which often attempt to stoke outrage in an effort to divide Western societies. In a nod to COVID-era social distancing, disinformation expert Nina Jankowicz has promoted the concept of “informational distancing”—stopping to question sensationalist claims—to slow the “viral”spread of disinformation. Disinformation experts coined the mnemonic SIFT, a reminder to “Stop, Investigate the source of information, Find better coverage, and Trace claims, quotes and media to the original context.”

Protecting oneself against Putin’s psychological warfare is an important step in protecting the values of a free society.

For Further Reading:

Some good biographies of Putin include the following:

Mark Galeotti, We Need to Talk About Putin, Ebury Press, 2019.

Fiona Hill and Clifford G. Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, Brookings Institution Press, 2015.

Catherine Belton, Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2020.

Masha Gessen, The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin, Penguin, 2013.

August 22, 2023: Clarified wording on Women’s March

July 25 2024: Added a note about Soviet-born German writer Wladimir Kaminer’s comments that the film, though ostensibly set in Nazi Germany, held up a mirror to Soviet society.