When Privileged Access Falls into the Wrong Hands: Chinese Companies in Microsoft’s MAPP Program

Chinese companies face conflicting pressures between MAPP’s non-disclosure requirements and domestic policies that incentivize or mandate vulnerability disclosure to the state.

On July 25, 2025, Bloomberg reported that Microsoft is investigating whether a leak from its Microsoft Active Protections Program (MAPP) allowed Chinese hackers to exploit a SharePoint vulnerability before a patch was released. Microsoft attributed the campaign – dubbed “ToolShell” after the custom remote access trojan used – to three China-linked threat actors: Linen Typhoon, Violet Typhoon, and Storm-2603. The attackers reportedly compromised over 400 organizations worldwide, including the U.S. National Nuclear Security Administration.

Launched in 2008, MAPP is designed to reduce the time between the discovery of a vulnerability and the deployment of patches. By giving trusted security vendors early access to technical details about upcoming patches, Microsoft enables them to release protections (such as antivirus signatures and intrusion detection rules) in sync with its monthly updates. The program, however, relies on strict compliance with non-disclosure agreements and the secure handling of pre-release data.

Concerns about some Chinese companies violating MAPP requirements are longstanding. In 2012, Microsoft removed Chinese company Hangzhou DPTech Technologies Co., Ltd. (杭州迪普科技股份有限公司) from the program for violating its nondisclosure agreement (NDA). According to Bloomberg, in 2021, Microsoft suspected that at least two other Chinese MAPP partners leaked details of unpatched Exchange server vulnerabilities, enabling a global cyber espionage campaign linked to the Chinese threat group Hafnium. The Microsoft Exchange hack affected tens of thousands of servers, including systems at the European Banking Authority and the Norwegian Parliament, and was met with global condemnation. Although Microsoft said it would review MAPP following the incident, it remains unclear whether any reforms were implemented, or whether a leak was ever confirmed.

In light of the SharePoint case, this piece examines how MAPP operates, the risks posed by Chinese firms in the program, and which companies are currently involved.

MAPP Seeks to Reduce Risk Through Early Disclosure

The core purpose of MAPP is to minimize the window of risk between patch rollout and deployment. Simply releasing a patch doesn't mean systems are protected: many organizations delay patching, and attackers often exploit known vulnerabilities during this lag. By giving trusted vendors early access to vulnerability details, Microsoft ensures they can build and distribute detection signatures and other defensive measures in advance, so these protections are already active when the patch is published. Without MAPP, vendors would only begin creating protections after public disclosure, leaving many systems globally, including in China, exposed for critical hours or days.

To participate in MAPP, security vendors must meet criteria that demonstrate their ability to protect a broad customer base. Applicants must be willing to sign a non-disclosure agreement, commit to coordinated vulnerability disclosure practices, share threat information, and actively create in-house security protections such as signatures or indicators of compromise based on Microsoft's data. Microsoft retains discretion over admission and may suspend or expel members who fail to meet participation standards.

According to the MAPP website, members are divided into three tiers based on the amount of time they receive vulnerability information before public release and other criteria: Entry (24 hours in advance), ANS (up to 5 days in advance), and Validate (invite-only, focused on testing detection guidance). However, recently admitted MAPP partners and recognized experts have observed that Microsoft may provide critical vulnerability and threat intelligence as early as two weeks prior to public disclosure. Criteria for determining the criticality which warrants such early releases and to whom the intelligence flows is unclear.

Risks of Chinese Participation in MAPP

Chinese companies operating within MAPP present a unique risk due to national regulations mandating the disclosure of vulnerabilities to the state. In September 2021, China implemented the Regulations on the Management of Network Product Security Vulnerabilities (RMSV), which require any organization doing business in China to report newly discovered zero-day vulnerabilities to government authorities within 48 hours. This gives Chinese state agencies early access to high-impact vulnerabilities – often before patches are available. Microsoft itself acknowledged the implications of this policy in its 2022 Digital Defense Report, noting that “this new regulation might enable elements in the Chinese government to stockpile reported vulnerabilities toward weaponizing them.”

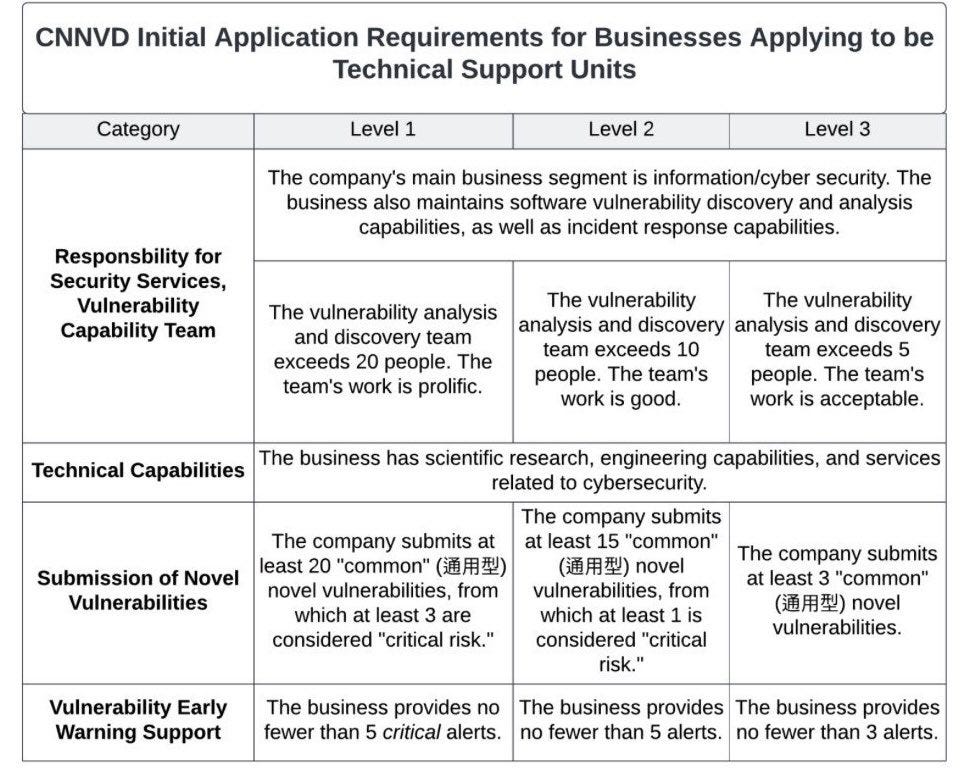

While the RMSV serves as the primary legal pathway for the state to acquire zero-days, it is not the only mechanism. In 2023, cybersecurity analysts Dakota Cary and Kristin Del Rosso uncovered a parallel, more opaque process involving the China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD), which is overseen by the Ministry of State Security (MSS). Under this framework, Chinese cybersecurity firms voluntarily partner with CNNVD to report vulnerabilities, in exchange for financial compensation and prestige. These firms, known as technical support units (TSUs), are stratified into three tiers based on the number of vulnerabilities they submit each year. Tier 1 TSUs must submit at least 20 “common” vulnerabilities annually, including a minimum of 3 classified as “critical risk.”

As early as 2017, the U.S. threat intelligence firm Recorded Future demonstrated that vulnerabilities reported to CNNVD are assessed by the MSS for their potential use in intelligence operations. As of this writing, 38 companies are classified as Tier 1 contributors to CNNVD, 61 as Tier 2, and 247 as Tier 3. Of these, ten Tier 1 companies, one Tier 2, and one Tier 3 company are currently MAPP members.

In addition to providing new vulnerabilities to the CNNVD, TSUs are also required to provide “vulnerability early warning support” to the MSS: at least five “critical alerts” annually for Tiers 1 and 2, and at least three for Tier 3. As cybersecurity and tech companies, many TSUs likely provide this early warning support by reporting newly observed attacks on their customers or systems. Nothing beyond the Microsoft NDA precludes TSUs from sharing MAPP data with CNNVD, which may view such submissions as fulfilling this vulnerability early warning support requirement.

Chinese MAPP Participants Dominated by CNNVD Tier 1 Companies

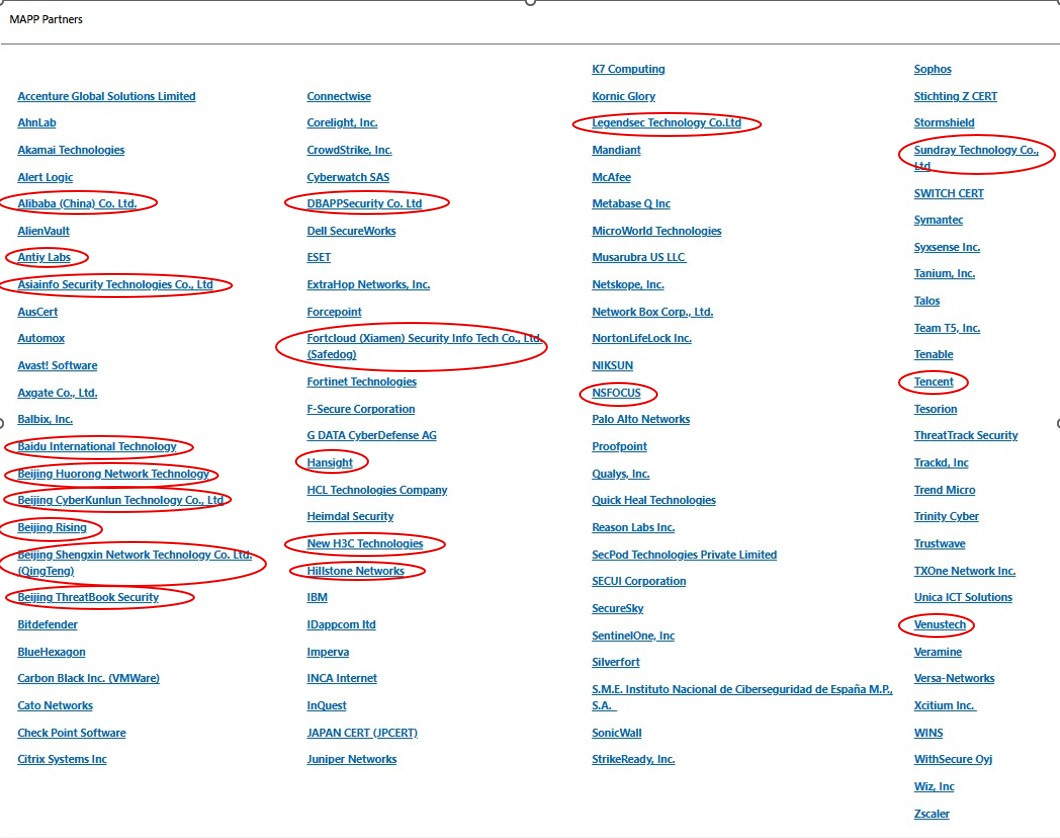

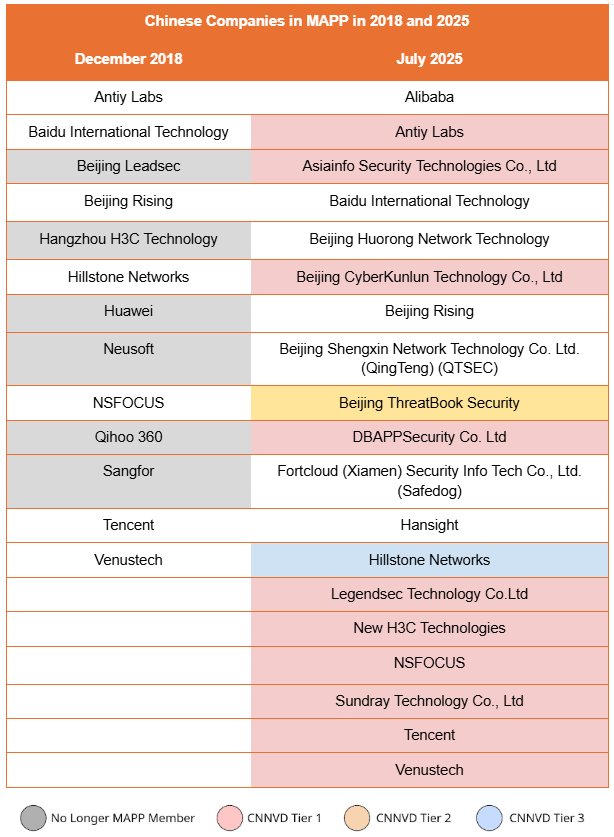

Our analysis of the MAPP main page via the Wayback Machine shows that the number of Chinese companies listed in MAPP increased from 13 in December 2018 (the earliest available snapshot) to 19 out of a total of 104 member companies globally as of this writing – the second-largest national representation after the US.

Since 2018, several Chinese companies have appeared and disappeared from the MAPP list. Companies that have since disappeared include Beijing Leadsec (北京网御星云技术有限公司), Huawei, and Neusoft (东软集团) (removed between December 2018 and November 2019), Qihoo 360 (奇虎360) (between November 2019 and October 2020), Hangzhou H3C Technology (between December 2021 and October 2022), and Sangfor (between October 2022 and September 2023). Newly added companies between 2018 and today can be seen in the table below. The reasons for a company's removal from the MAPP list are not always clear. In the case of Huawei and Qihoo 360, the timing aligns with their addition to the U.S. Entity List in 2019 and 2020, respectively. For others, we could not locate any public explanation from Microsoft, unlike the 2012 public notice from the Microsoft Security Response Center regarding DPTech’s removal for violating MAPP’s NDA requirements.

Of the 19 Chinese companies currently participating in MAPP, 12 are classified as CNNVD TSUs (see table below). Based on previous research into their vulnerability submissions to Microsoft’s bug bounty program, Tier 1 TSUs such as Tencent (腾讯), Cyber Kunlun (赛博昆仑), Sangfor (深信服科技), QiAnXin (奇安信), and Venustech (启明星辰) operate dedicated labs – with varying levels of focus – on identifying vulnerabilities in Microsoft software products.

It is also possible that individuals working at MAPP companies in China individually decide to pass along or sell such information to offensive teams. With access to valuable information and a clear market of buyers, insider risk at MAPP partners themselves cannot be ruled out.

Regardless of the specific mechanism for information diffusion, it is clear that China’s incentives for reporting such vulnerabilities – both economic and reputational, as companies seek to meet CNNVD quotas and maintain TSU status for potential business opportunities – create an environment which incentivizes abuse.

China’s Vulnerability Ecosystem Enables Rapid Exploitation and Cross-Group Sharing

Vulnerabilities reported to the MSS-run CNNVD may be evaluated for potential operational use before being disclosed to the public. Chinese APT groups are known for their speed and coordination in exploiting such vulnerabilities. According to advisories from multiple national cybersecurity agencies and threat intelligence firms, groups such as APT40 and APT41 have exploited vulnerabilities within hours or days of public disclosure. Chinese APTs are also effective at sharing exploits across groups. Once a vulnerability has been successfully weaponized, it often circulates rapidly among operators.

Both of these dynamics were on display during the 2021 Microsoft Exchange campaign. On February 23, 2021, MAPP distributed proof-of-concept (POC) code to its members so they could engineer detections. Five days later, mass exploitation of the vulnerabilities with similar code to that distributed via MAPP blanketed the web. According to threat intelligence firm ESET, exploitation began with the China-linked threat group Tick and was quickly followed by other China-linked groups, including LuckyMouse, Calypso and the Winnti Group. Microsoft made patches publicly available for customers shortly thereafter on March 2, 2021–seven days after distributing POC code to MAPP members.

A similar pattern emerged in 2025 with the exploitation of SharePoint vulnerabilities first disclosed at Pwn2Own Berlin in May. The winning submission was reported to Microsoft shortly after the event. As per standard MAPP procedures, Microsoft distributed vulnerability details to selected partners up to two weeks before the public patch, scheduled for July 9. Yet CrowdStrike observed exploitation as early as July 7, again suggesting that threat groups may have gained access to vulnerability details before protections were made widely available. Microsoft attributed the activity to no fewer than three China-linked groups on July 22.

Mission or Mission Impossible?

Microsoft’s stated mission is to “empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more.” In line with this mission – and given Microsoft’s strong global presence, including a vast userbase in China – initiatives like MAPP play a critical role in protecting users from malicious actors. However, such programs require strong safeguards and clear accountability, and ensuring full compliance can be difficult. In unique contexts such as China’s centralized vulnerability disclosure system, the inclusion of Chinese companies warrants special scrutiny, especially those participating in domestic programs that incentivize reporting vulnerabilities to the state.

Unfortunately for Microsoft’s userbase in China, the government incentivizes behavior which should jeopardize the continuing participation of legitimately defensive companies in MAPP. It is the role of the PRC government to enforce laws on companies operating within its jurisdiction and responding to its policies. In consideration of Microsoft’s pursuit of adequate defense and support of its users, and in line with the company’s mission statement, it may be appropriate for Microsoft to temporarily suspend PRC-based companies from MAPP pending an investigation by the PRC government into the potential violation of Microsoft’s NDA with local companies. Microsoft has the systemic importance to request such an investigation, as the behavior clearly jeopardizes the safe operation of Critical Information Infrastructure under the PRC Cyber Security Law.

Concise and clear. Well done

Top