Few and Far Between: During China’s Red Hacker Era, Patriotic Hacktivism Was Widespread—Talent Was Not

Inside the small, elite circles that powered China’s massive hacker communities in the late 1990s and 2000s.

This post is excerpted from the Cyberdefense Report "Before Vegas: The ‘Red Hackers’ Who Shaped China’s Cyber Ecosystem," published in July 2025 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich, Switzerland.Truly elite offensive cyber talent has always been rare. Despite the growth of cybersecurity communities worldwide, and the emergence of extensive and structured talent pipelines in countries like China – examined in Natto pieces 1, 2 and 3 – which have made high-quality talent more widely available, truly exceptional individuals remain scarce and highly sought after.

As early as 2013, the Science of Military Strategy—a foundational text published by the PLA Academy of Military Science—noted that while cyber warfare benefits from a “broad mass base,” the traditional Chinese military ideal of “all people are soldiers” does not translate to cyberspace. Instead, it emphasized that only an “extremely lean” cohort possessed the capabilities required for high-level cyber operations.1

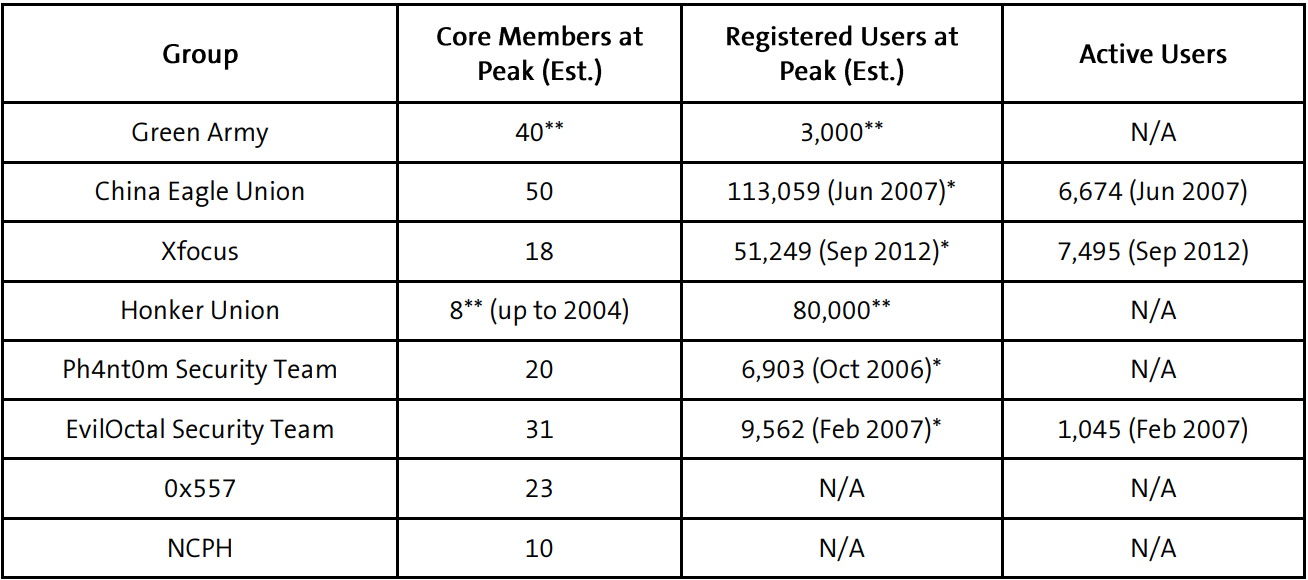

Prominent Chinese “red hacker” groups2 active in online forums throughout the late 1990s and 2000s, such as the Green Army, the Honker Union of China, and the China Eagle Union, often boasted memberships in the thousands. The Green Army claimed around 3,000 members, the Honker Union 80,000, and an archived 2007 version of the China Eagle Union website listed over 113,000 registered users. Yet these large numbers masked the reality: the core teams responsible for actual operations typically included only a handful of technically proficient members.

This piece dives deeper into that history and examines how these hacker groups, despite their size, relied on a small, tightly knit circle of technically proficient individuals. It highlights the distinction between core members and registered users, the range of roles within the core teams, and their internal structures.

Many Registered Users, Few Core Members

At its peak in the late 1990s, the Green Army was estimated to have about 3,000 members, while the EvilOctal Security Team reported a peak of 9,562 members in 2006. The Honker Union of China was estimated to have around 80,000 members, and an archived 2007 version of the China Eagle Union website reported over 113,000 members.

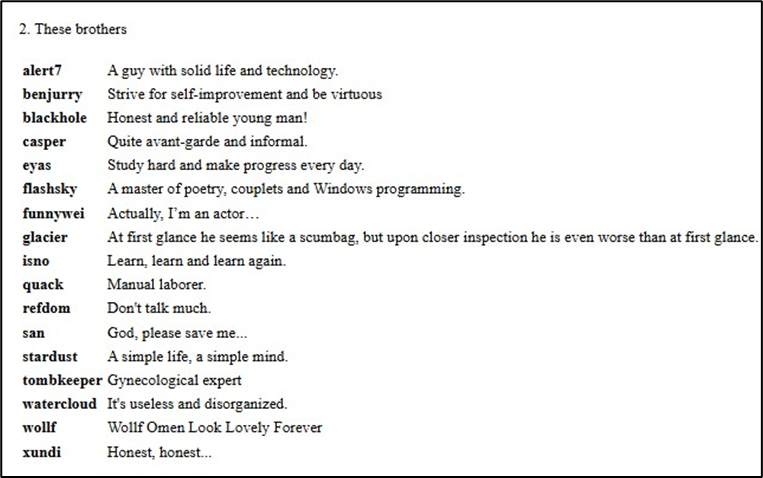

Despite these large numbers, a closer analysis of major group websites revealed significant variation in the roles and influence of these members. While internal structures differed by group, roles broadly fell into two categories: 1) core members and (2) registered users. Core members played central roles in group operations, including both technical activities (e.g., hacking) and non-technical functions such as human resources, finance, and logistics. Registered users, by contrast, primarily engaged in forum discussions. In a 2009 article, Wan Tao (万涛, eagle), founder of the China Eagle Union, differentiated between “main members” and “volunteers.” Similarly, EvilOctal maintained separate sections on its website for official team members and for forum users.

The core membership of these groups was likely small. In a 2018 blog post and article in "The Development History of Chinese Hackers," Green Army founder Gong Wei (龚蔚, goodwell) mentioned that between 1997 and 2000 the Green Army had around 40 team members, with reportedly around 3,000 registered users overall. The Honker Union of China provides a similar example. While commonly cited as having 80,000 registered users, core membership was likely far smaller. A 2009 article "A Top-Secret Analysis of China’s Hacker X-Files," posted on the webpage of the Changzhou Computer Information Network Security Association (常州市计算机信息网络安全协会), mentioned only eight core members in the Honker Union of China (HUC). Former HUC member “K,” remarked,

“truthfully, we were only five or six, and I was of course one of them. Very simply, those five or six people set up a website and started a forum, and then many others said they were members once they registered. As to the 80,000 numbers, I do not know how the counting was done for that report.”

Other groups examined in this report display a similar pattern. An archived 2005 version of the China Eagle Union’s website estimated approximately 50 core members (January 2005), and 113,000 registered users (June 2007).

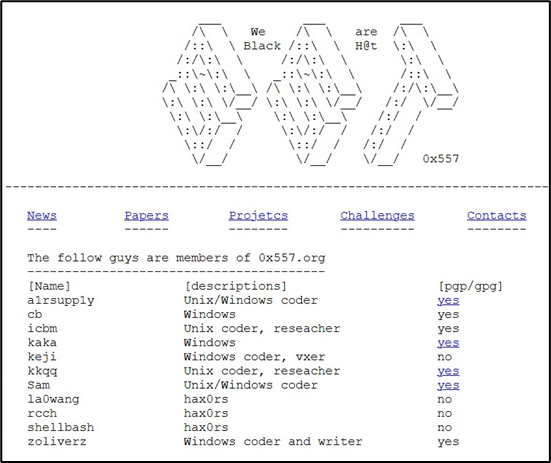

An archived version of the 0x557 website from October 2004 listed 11 core members, while two undated group photos posted in June 2018 on Anquanke, a Chinese platform for hacker and cybersecurity communities, suggest a membership of around 20. No information on registered users was found, as archived 0x557 sites identified for this report did not include a forum. NCHP listed 10 core members in 2005, with no available forum and data on registered users.

XFocus listed up to 18 core members across archived versions of its site from 2004 to 2012, with 50,000 reported registered users in September 2012. EvilOctal, by 2010, listed 31 core members—largely in line with the previous years—and reported 9,562 registered users on its archived website from February 2007. The Ph4nt0m Security Team listed between 11 and 20 core members between 2004 and 2009, with a peak of approximately 6,900 registered users recorded in October 2006.

Across these eight groups, the core membership totals approx. 200 individuals. While these estimates are based on data that was archived at irregular intervals and may not be entirely precise, they nonetheless highlight a consistent pattern: Red hacker groups often registered large memberships, but their operational cores likely remained small, tightly-knit, and relatively stable in size.

Easy to Join, Hard to Stand Out

Registered users typically joined through low-barrier processes, such as submitting an email address via the group’s website, with little to no identity verification or technical vetting. As Lin Juemin, an editor at the Chinese tech media platform Leiphone (雷峰网), noted in a 2022 article,

“to be honest, what everyone calls ‘joining the Green Army really just meant registering as a member on the website, without any formal or strong organizational affiliation.”

Many registrants were likely drawn into a group by curiosity and a desire to learn but also likely included enthusiastic amateurs and passive observers. These forums were often moderated by technically skilled core members and they served as platforms for technical discussions and as a way to stay informed about ongoing cyber campaigns — especially in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, since only a small subset of registered users was ever active during a given period, it remains difficult to determine the extent and nature of their participation.

It is likely that many registered users who did engage in hacking activities operated at a relatively low technical level. In 2005, Chu Tianbi, author of the 2005 “Chinese Hacker History/Looking Back on Chinese Hacker History,” noted that

“the lowering of technology barriers had led to the appearance of many young hackers, including high school students, armed with off-the-shelf tools and software despite having no technical knowledge.”

According to "A Top-Secret Analysis of China’s Hacker X-Files," the majority of the 80,000 members in the Honker Union of China (HUC) lacked even basic networking knowledge, often relying on outdated methods such as spam emails and ping attacks. The analysis further stated that “it was later revealed to be nothing more than a group of kids playing at hacking. Exaggerated by the media, it turned into a farcical ‘patriotic show.’”

By contrast, becoming a core member required a higher technical standard and typically involved a more structured, selective process—which varied from group to group.

Membership Was Mixed, but Skilled Hackers Sat at the Top

Despite being central to the group’s activities, core membership was not constrained to hacking roles. The Green Army’s core members also included translators, webmasters, and even textbook authors. Other groups, such as HUC, counted network administrators, community organizers, and even one accountant as their core members. EvilOctal distinguished between various roles, including "think tank" contributors, journal editors, operations and maintenance staff, a technical core team, decision-makers, and team executives. These tasks were often taken on by highly skilled members themselves. Given the technical nature and mission of these groups—as reflected in the admission requirements for China Eagle Union and EvilOctal—members with hacking expertise were likely the most influential. EvilOctal, for instance, explicitly described its technically skilled core members as the “backbone” of the group.

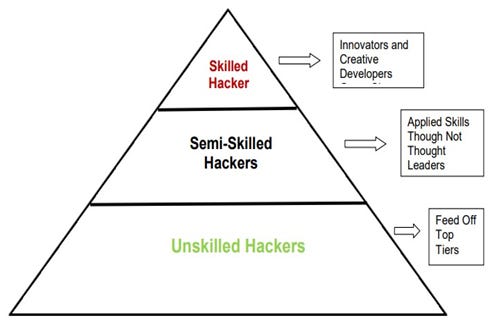

These internal dynamics are consistent with broader patterns identified in studies about the structure of hacker communities. In their 2012 study titled “Know Your Enemy: The Social Dynamics of Hacking” for the Honeynet Project, U.S.-based researchers Max Kilger and Thomas Holt described a pyramid structure with “highly skilled” members occupying the top, followed by “semi-skilled hackers”—both of which correspond roughly to the core members of red hacker groups. At the base are “unskilled hackers”— a category likely analogous to the majority of registered users, as described by Chu Tianbi and "A Top-Secret Analysis of China’s Hacker X-Files" — that feed off from the top tiers.

Little Technical Talent Likely Rooted in Poor Talent Development Structures

Despite their importance, the number of highly skilled hackers within red hacker groups was likely small. In some cases, the lack of enough technical talent proved a challenge to the group’s ability to function—at times even threatening its survival. In 2004, HUC’s leader Lin Yong (林勇, lion) acknowledged the group's lack of enough technical talent in his farewell message:

“To be truthful, the Honker Union of China has been surviving in name only… Talking about the technical side, there have been only three people providing technical support for the Honker Union of China, bkbll (online name), uhhuhy (online name), and myself.”

At the time, identifying and maintaining a large skilled hacker base was likely impractical. The groups’ limited resources, as well as the absence of structured talent development and evaluation systems—made it difficult to accurately assess a person’s true capabilities. Instead, talent was often evaluated based on self-reported achievements, public contributions, and personal connections. Commenting on the real core of skilled technical personnel within the China Eagle Union, its leader Wan Tao (万涛, eagle) put the number between 30 and 50, explaining that he simply “lack[ed] the time, energy, and resources to conduct a broader evaluation” of those who joined.

For a comprehensive discussion of the “extremely lean” concept and China’s approach to integrating highly skilled personnel into its cyber combat forces, refer to Chapter 8: “China Builds Offensive Capability with Military, Government, and Private Sector Forces” in The Emergence of China’s Smart State.

Red hacker groups” refers to loosely organized Chinese hacker collectives that, while operating independently, often align with state interests by targeting foreign entities perceived as hostile to China—such as the United States, Taiwan, and Japan. The term “red hacker” or “Honker” (Hong Ke, 红客) consolidated in the late 1990s and early 2000s, popularized by the Honker Union of China, the most well-known group of its kind. It remains in use in China today to describe acts of patriotic hacking. The Natto Team has discussed honkers here https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/stories-of-a-chinese-hacker-from here https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/defense-through-offense-mindset-from, and here https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/zhou-shuai-a-hackers-road-to-apt27

before "Vegas" + after "Vegas" = you should make a book! Great!