Ransom-War In Real Time, Case Study 1: Conti, EvilCorp and Cozy Bear

In 2020-2021 the Conti and EvilCorp ransomware groups helped Russian intelligence with espionage and possibly a hack-and-leak operation. Could they be contract teams for APT29 itself?

Introduction:

Previous installments of our “Ransom-War” series1 set the context for Russian cybercriminal/intelligence interaction by showing that Russian ransomware criminals do not operate in a vacuum and that the Russian political context colors everything they do. This helps explain why, in at least some cases, the ransomware actors allow themselves to be coopted for operations in Russia’s hybrid war against Ukraine and the West.

Skeptics of the Natto Team’s “hybrid ransomware” thesis have raised numerous important questions: Can Russian cybercriminals seriously be receiving direct government tasking? If so, how do they communicate? Or are they improvising based on more diffuse “patriotic entrepreneurialism”? If so, how do they know what Putin’s government wants them to do and when? Whether they receive direct instructions or improvise, how could criminals unleash ransomware on short notice? More broadly, how can Russian intelligence services work with such an unruly bunch? Who holds the upper hand? The “Ransom-War” series attempts to answer these questions based on publicly available information.

In the case studies that follow, we seek more granularity on Russian criminal/intelligence interactions in specific operations, asking where the incidents fit on cybersecurity researcher Jason Healey’s “spectrum of state responsibility” for cyber operations (see “Ransom-War” Part 1), and what role they play in Russia’s hybrid warfare against Ukraine and the West.

In this posting, we return to the case of the Conti ransomware group (also known as the Wizard Spider or Trickbot group) and also look at Evil Corp, both of which are known to cooperate with intelligence services. We focus on their real-time mechanisms of interaction with state officials.

We find that this cooperation sometimes involves data sharing for espionage and/or hack-and-leak operations.

We find a common modus operandi, where criminals perform initial breaches of many machines as part of their regular extortion operations, but then the intelligence agencies piggyback on them for further operations, whether espionage or cyber-enabled information operations.

Then we explore these two groups’ relationship with the SVR hacker group Cozy Bear (APT29). In at least one incident, an Evil Corp ransomware attack appears to have been directly connected with the 2020 SolarWinds supply-chain espionage operation, which the US and UK governments have attributed to the SVR. Evidence on that operation unearthed in 2021 by cybersecurity researchers at Prodaft, Truesec and Analyst1 allow us to hypothesize that Evil Corp and the Conti group may indeed play integral roles in the APT29 operating model.

In subsequent postings we will apply these findings to provide plausible scenarios for real-time criminal/intelligence interaction in other ransomware operations where the relationship is not as clear, such as the 2019 attack on NorskHydro — in which Russian intelligence may have played a role in stimulating the development of destructive ransomware.

See below for an update made October 3 2024 with information the US and UK government provided when announcing new sanctions and indictments of Evil Corp members on October 1 2024. In addition, this posting has been updated with further analysis from Conti’s operation against Academi.

Conti/Trickbot/Wizard Spider:

A group commonly known as the Conti or Trickbot group or Wizard Spider, and associated with malware families Trickbot, Conti, and Ryuk, is well-known to work with the Russian government. As the US Treasury said in a February 9, 2023 sanctions document: “Current members of the Trickbot Group are associated with Russian Intelligence Services. The Trickbot Group’s preparations in 2020 aligned them to Russian state objectives and targeting previously conducted by Russian Intelligence Services. This included targeting the U.S. government and U.S. companies.”

Granular information on that relationship comes from several different leaks of Conti communications, leaks that multiple analysts consider to be reliable sources.2

In previous Natto Thoughts postings, we saw that several top group members would solicit paid or unpaid assignments from at least two offices, apparently referring to local offices of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) and the Federal Security Service (FSB). Group leaders did not share specific information about these government contacts with lower-level group members. This caginess — a good practice for operational security — also created an atmosphere of rumor and intrigue that likely bolstered the group leaders’ cachet.

Operational security was necessary, as group members did not know how much government protection they could count on. They perceived themselves as navigating between friendly and less-friendly Russian special services, using bribes when necessary to evade punishment. Top member “Silver”3 assured member “Brooks” in November 2021 chat that the FSB and SVR were likely sympathetic or neutral toward the group, but that the MVD (Russia’s police force) might harass them, because the Russian police “have been bought, lock stock and barrel, by the Amers [Americans]....and they work on the side as private detectives, suckling at the breast of the American special services [на подсосе у амерских спецслужб].” (Recall that this was during a period of ostensible cooperation between US and Russian law enforcement). Silver noted, however, that a well-priced bribe can mollify even the police: he told Brooks that, if called in for questioning, “You need to resolve the question right there; the price tag will be about 10-50k,” with “k” presumably referring to thousands of rubles.

The government sponsors appear to have given the group specific wish-lists or guidance for the group’s targeting. In July 2020, group member “professor”4 said his paying contacts in the SVR “really want COVID-related [things] right now, (по ковиду они хотят щас очень)” likely referring to information on vaccine development or on target countries’ failed responses to the pandemic. The Conti group also spied on members of the Bellingcat investigations network, apparently on FSB request.

The group’s modus operandi fits our definition of a hybrid ransomware operation; government clients piggybacked off of the crime group’s financially motivated everyday work of breaching systems. “Professor” reported in 2020 that Cozy Bears (Apt29) operatives were looking through a list of some kind. They may have been looking through a roster of entities that Conti operatives had compromised, in order to identify targets for deeper CozyBear espionage. As mentioned in Part 1 and Part 2 of the Natto Thoughts “Ransom-War” series, member “Target” planned to set up a whole office “for government topics” (под гос темы) that would go through previously stolen foreign government documents and find ones that would interest potential Russian government sponsors. This resembles how FSB officials worked with Russian cybercriminals to obtain intelligence from a 2014 hack of Yahoo, as detailed in a 2017 US indictment.

Academi Hack, 2020: Espionage assignment and possible hack-and-leak

In one incident reflected in the Conti/Trickbot leaks, group members breached a company with national security significance, then a government sponsor gave them real-time guidance on what information to search for in the victim company’s systems. Although no actual encryption or extortion is known to have occurred, the incident appears to have ended with a hack-and-leak operation. This was a July 2020 breach of US private military company and government contractor Academi (formerly Blackwater), also known as Constellis. The italicized text below was added/updated on September 24 2024.5

On July 15 2020: “Target” boasted to Conti boss “Stern,” “I have good news for you.” He quoted a message – which appears to have come from Maze actors -- saying that Academi and its subsidiaries Triple Canopy, Olive Group Capital Ltd., and Strategic Social LLC, as well as over 30 other military related entities and the US Environmental Protection Agency, had been breached.

Target did not divulge to “Stern” that the group was already facing challenges in exploiting these breached systems. The previous day Target had privately instructed tester “Dandis” to work on Academi and said “Prof” – presumably “Professor” -- could help him. Then, only a few hours before Target spoke with Stern on July 15, “Dandis” had reported back to Target that “Prof” had been unable to escalate privileges within the Academi systems. “He will pass along the [breached] network to another person who will try to escalate privileges.” Target said, “Thx. Today we will attack them, very soon. We already agreed with contacts so you will launch from a different PC (прыгнули с другого пк).” It is unclear whether he planned to attack Academi or was talking about a different operation.

On July 20 2020 Conti member “Professor” asked, “What do we need from Academi? Did one of the two offices ask for it?” likely referring to Russian intelligence services offices. Stern said “yes” and indicated that the client wanted to see correspondence, contracts, and bookkeeping information from the breached Academi systems. It was during that conversation that Professor asked whether they would get paid or would “play Pioneers,” and Stern responded, “who cares about money,” after which Professor said he had someone in a foreign-intelligence service who would pay for any interesting information.

On July 22 2020 Stern asked member “revers” whether they had exfiltrated data from Academi yet. Revers replied that they needed to wait a few days so the [Academi] administrators would calm down, plus the IDS was very complicated and Revers was “afraid I will fuck it up” and wanted to wait for “prof” before proceeding.

On July 23 Target told Dandis that everyone was in panic “over there,” likely referring to Conti group headquarters.6 ”At first it was OK, but then it’s ‘hurry up, hurry up!’,” Target said. Dandis responded, “Ah, sad.” Target said “It’s nothing, we’ll figure it out somehow. With Academi we were f**king around for almost a year,” apparently meaning that the group had worked for almost a year to obtain access to Academi systems and finally managed to do so. Target might be trying to make Dandis feel better about the difficulties he was encountering in exploiting Academi systems, by pointing out how long these operations take. The reason for the panic and haste is unclear, but one plausible explanation is that the group felt they had been, or might be, discovered in Academi’s systems and had to exploit them quickly and get out.

The Academi breach is not publicly known to have ended in ransomware; the Natto Team could find no public acknowledgements from 2020 of any cyber incidents or data breaches involving Academi or any of its other names.7

However, less than two weeks after these discussions among Conti members, a large trove of data appeared on the website of US-based transparency organization DDoSecrets. On August 3, 2020 DDoSecrets advertised “268 megabytes in 115 files dated 2017 and 2020 from Constellis, a.k.a. Academi, a.k.a. Blackwater.” The entry on DDoSecrets’ website gives no clue as to who sent them the leak. However, the close timing suggests it had something to do with the Maze/Conti breach of that organization.

A possible scenario for this might be as follows:

Conti breached the company with help from the Maze group;

Someone from “the two offices,” likely Russian intelligence agencies, requested certain information from it but did not pay Conti;

Apparently following some kind of scandal, unmasking or other setback between July 15 and July 23, Conti did not try to force the organization to pay ransom;

Instead Conti leaked the information on DdoSecrets for free.

The choice of a transparency organization like DDoSecrets points to the political motivation of the operation. Such a public leak was irreversible, so the hackers were apparently not expecting to receive ransom from Academi. Rather, the leak might be expected to undermine the reputation of this controversial8 US military contractor and facilitate further scrutiny of it by both social activists, investigators, and state-linked people in any country. This brings wider publicity for the ransomware actors, greater risk for the victims of their activity, and national security threats. Ransomware actors Snatch and Clop (Cl0p) would subsequently share stolen date with DDoSecrets.9

This incident overlaps with the phenomenon of state-aligned ransomware actors posing as idealistic hacktivists. The Natto Team and other analysts have explored this overlap between ransomware and pseudo-hacktivism in the past few years. The Academi incident suggests this ransomware/hacktivist overlap began at least by 2020.

Evil Corp:

In Part 3 of the Ransom-War series we pointed to 2016-2017 as the year when Russia’s GRU military intelligence agency spoke of using ransomware to bring down entire countries and experimented with its own pseudo-ransomware attacks on Ukraine. 2017 also appears to be the year when the FSB began experimenting with coopting real ransomware criminals as opposed to fake personas.

Evil Corp (a.k.a. TA505) is a Russian criminal group that developed malware strains including Locky, Dridex, WastedLocker, Hades, SocGholish (FakeUpdate), BitPaymer and others. In 2019 the US Justice Department indicted its leader, Maksim Yakubets (a.k.a. “aqua”), and other group members. The US Treasury Department sanctioned Yakubets and said that he had worked for the FSB since at least 2017 and that, as of April 2018, he had applied for FSB certification to deal with state secrets. Treasury said, “Yakubets was tasked to work on projects for the Russian state, to include acquiring confidential documents through cyber-enabled means and conducting cyber-enabled operations on its behalf.” A reporter for an independent Russian news source also found evidence of Evil Corp as a contractor for the FSB: “One of my sources, who is an ex-FSB officer, told me that he personally tried to enlist some of the guys from Evil Corp to do some work for him.” It may be no coincidence that EvilCorp’s ransomware-as-a-service operation launched in 2017.

Russian law enforcement had known about Yakubets’ criminal work for many years. Back in 2009 or 2010, Russian FSB agents themselves revealed his identity to the US FBI, according to former FBI agents who worked on the case (minute 23:33 of their podcast), but the FSB did not bring him to justice. Instead, they hired him. This is consistent with Russian intelligence services’ practice of bringing criminals into the station for “prophylactic chats,” telling cybercriminals that the FBI is after them and pressuring them to work for the FSB instead. (The changing motivations and relationships between Russian and US law enforcement are a story in themselves, discussed in “Ransom-War” Part 4b and elsewhere). The FBI would publicly identify “aqua” as Yakubets in 2019.

Yakubets and EvilCorp have not only contractual ties with the FSB but family ties as well. In that same fateful year of 2017, in a lavish wedding, Yakubets married the daughter of a retired FSB official named Eduard Bendersky. Bendersky is a top member of the Vympel Association of Former FSB Spetsnaz Officers. That is the group that recruited contract killer Vadim Krasikov for the famous 2019 assassination of former Chechen insurgent Zelimkhan Khangoshvili in Berlin; Bendersky himself reportedly supervised that operation. Russian President Vladimir Putin apparently valued assassin Krasikov highly; after Germany imprisoned Krasikov, Putin’s representatives engaged in nearly two years of tortuous negotiations over a prisoner swap, eventually agreeing to release numerous dissidents held in Russian prisons in return for Krasikov’s release.

Personal attraction aside, Yakubets’ marriage to Bendersky’s daughter would have advantages for both sides. Yakubets gained a protector, of the kind discussed in Natto Thoughts posting Ransom-War Part 4a. For his part, Bendersky – who appears to have a line of business in coopting criminals for FSB tasks – gained leverage over FSB. The lavish wedding likely bolstered their street cred in their respective communities.

Update October 3 2024: On October 1, 2024, a raft of announcements by US, UK and Australian authorities provided further evidence of the Evil Corp group’s relationship with the Russian state.

The US Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) provided stunning evidence of how high Yakubets’ protection went. In an announcement of supplementary sanctions against Evil Corp members, issued in alignment with the UK and Australia, OFAC wrote that Maksim Yakubets’ FSB-veteran father-in-law, Eduard Benderskiy,

leveraged his status and contacts to facilitate Evil Corp’s developing relationships with officials of the Russian intelligence services. After the December 2019 sanctions and indictments against Evil Corp and Maksim, Benderskiy used his extensive influence to protect the group….both by providing senior members with security and by ensuring they were not pursued by Russian internal authorities.

Yakubets and Bendersky pursued business with current and former high officials in Russian government, according to OFAC. Yakubets

used his employment at the Russian National Engineering Corporation (NIK) as cover for his ongoing criminal activities linked to Evil Corp. The NIK was established by Igor Yuryevich Chayka (Chayka), son of Russian Security Council member Yuriy Chayka, and his associate Aleksei Valeryavich Troshin (Troshin). In October 2022, OFAC designated Chayka, Troshin, and NIK pursuant to E.O. 14024.

When imposing the sanctions in 2022, the OFAC further detailed that Evil Corp’s Yakubets “was involved in setting up the NIK offices and its hiring practices” and that, “As part of his activity at NIK, Yakubets continued his work on behalf of the Russian intelligence services.” Since the OFAC first imposed sanctions on Yakubets in 2019, “Yakubets has since developed a relationship with all three major Russian intelligence services, including personally meeting with SVR Director Sergey Naryshkin.”

Yuriy Chayka, the father of Yakubets’ boss, is not only a Russian Security Council member, but a former Russian Minister of Justice (1999-2006) and Prosecutor-General (2006-2020). The son founded the NIK company in 2018, and by 2021 NIK was offering services for combating cybercrime, according to the relatively independent Russian business periodical Kommersant.Thus, Yakubets was hiding among people associated with Russia’s own legal system.10 Commenting on Evil Corp and its relationships, shown by the recent sanctions, UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy said, “Putin has built a corrupt mafia state with himself at its centre.”

The UK’s National Crime Agency provided more detail on Yakubets’ criminal history.

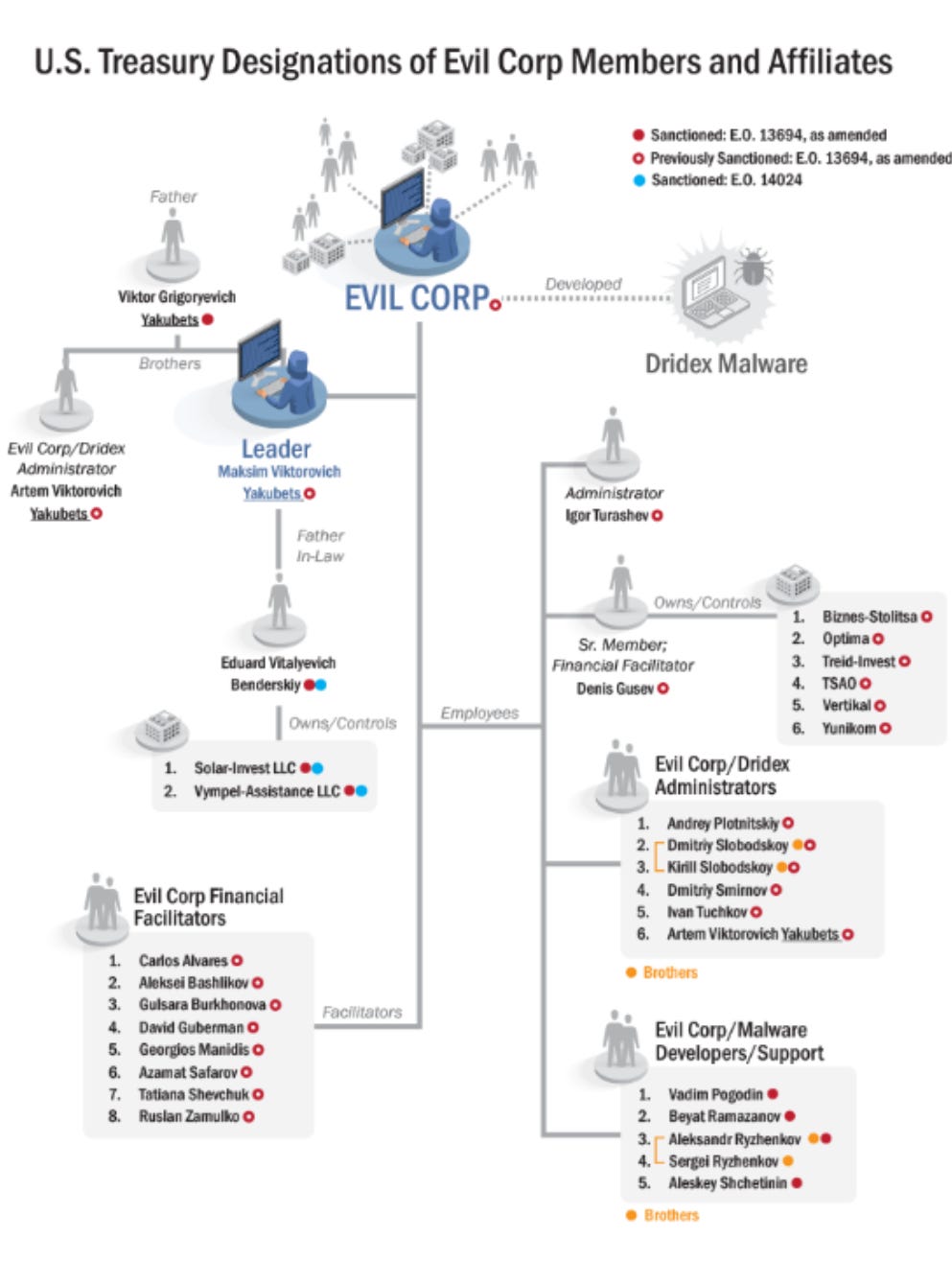

The NCA report also pointed out that Evil Corp operates like a family-based organized crime gang, incorporating Yakubets’ father, two brothers, and two cousins, in addition to his FSB-linked father-in-law.11 The OFAC sanctions document illustrates these relationships:

Connection with SVR-Linked Threat Group APT29: The SilverFish Operation

Evidence on the specifics of Evil Corp’s work for Russian intelligence services was unearthed in 2021 by cybersecurity researchers at Prodaft, Truesec and Analyst1, who studied the 2020 SolarWinds supply-chain espionage operation, which the US and UK governments have attributed to the SVR, and which Mandiant explicitly linked to SVR-linked threat group APT29 (a.k.a. Cozy Bear). These analysts raise the possibility that Evil Corp and the Conti group may indeed be integral parts of the APT29 operation.

On March 17 2021 Prodaft reported on a “global cyber-espionage campaign, which has strong ties with the SolarWinds attack, the EvilCorp, and the Trickbot group” and which affected at least 4720 targets. Prodaft refers to this “extremely well-organized cyber-espionage group” as “SilverFish” but refrains from attributing Silverfish activity to APT29 or any one group. The campaign they describe continued in several waves well into 2021, even after the SolarWinds campaign came to public knowledge in December 2020.

Prodaft went “behind enemy lines” in a SilverFish command and control (C&C) server. They found that SilverFish heavily targeted the US and focused on critical infrastructure entities, mostly in government, defense-related industries or energy but not “universities, small companies or systems which they consider worthless.” Prodaft also discovered links between EvilCorp, the Conti/Trickbot group, and SilverFish: “the same servers were also used by EvilCorp (aka TA505) which modified the TrickBot infrastructure for the purpose of a large scale cyber espionage campaign.” Prodaft argued that SilverFish consisted of “multiple groups with different motives” and used tools and infrastructure “that had been previously attributed to different groups and campaigns such as Trickbot, EvilCorp, SolarWinds, WastedLocker, DarkHydrus, and many more.”

Prodaft found that SilverFish actors operated during regular weekday working hours and in a hierarchical and compartmentalized environment.

SilverFish uses a team based workflow model and a triage system similar to modern project management applications like Jira. Whenever a new victim is infected, it is assigned to the current ‘Active Team’ which is pre-selected by the administrator. Each team on the C&C server can only see the victims assigned to them.....

During our investigation, we found four different teams (namely 301, 302, 303, 304) who were actively exploiting the victims’ devices. These teams cycle frequently almost every day or every two days....the C&C source code....statically contains nicknames and ID numbers of 14 people who most likely work under the supervision of 4 different teams.

Stockholm-based cybersecurity company Truesec dug deeper into SilverFish’s connection with ransomware group EvilCorp, which Prodaft’s public report had briefly mentioned. According to Truesec, in an October 2020 operation, Evil Corp attackers used a drive-by compromise (in which a target visits a compromised legitimate website and unwittingly downloads malware) to gain access to a major corporation. The EvilCorp actors established “complete control of the victim machine” within hours, suggesting that they “must have been continuously monitoring their C2 servers for new victims and immediately begun manual operations after they were alerted to a new victim.” The threat actors waited a week to do internal reconnaissance and uninstall security software. Then they spent nearly three more weeks gathering data and deleting cloud-based backups before deploying Evil Corp’s Wasted Locker ransomware. The victim company later received an email from a government cyber defense organization, implying that the attack on their system had was associated with the SilverFish espionage operation that Prodaft had described.

Truesec confirms similarities between the EvilCorp attack and the SilverFish operation. For example, Truesec notes, Prodaft reported that SilverFish “had teams of hackers working shifts, day and night. This certainly fits with our findings regarding the Wasted Locker attack in October. Only a group working continuously in shifts would be capable of reacting this fast to the successful drive-by attack.” The SilverFish actor apparently used existing infrastructure from the October 2020 EvilCorp attacks in order to “save as much as possible of the access obtained by the SolarWinds breach” after the breach came to public knowledge in December 2020.

Regarding EvilCorp, Truesec hypothesized:

Despite still deploying ransomware in attacks, the group no longer appears enticed by financial gain and, unlike other ransomware operators out there, does little to compel victims into paying the ransom.....It is possible that the entire Wasted Locker/Hades ransomware campaigns have been run as just a ‘maskirovka’, the Russian word for deception, to hide a cyber espionage campaign….

….Perhaps Evil Corp has now morphed into a mercenary espionage organization controlled by Russian Intelligence but hiding behind the façade of a cybercrime ring, blurring the lines between crime and espionage. If so, it would likely mean that this group uses the ransom money paid by victims to finance their espionage operations.

Following up on this report, Jon DiMaggio for Analyst1 hypothesized that, while it is possible that SilverFish was a separate group of actors who reused EvilCorp’s infrastructure, it is more likely that “Yakubets (and in turn EvilCorp) is or supports the SilverFish espionage group.” He assesses that the mysterious SilverFish group was in fact Cozy Bear itself, that in the SolarWinds operation “the FSB worked in conjunction with the SVR12 on a joint mission to compromise the United States government,” and that EvilCorp helped. “This demonstrates not only how Russian intelligence organizations work together, but also how Russia uses ransomware gangs to advance their offensive cyber capabilities against foreign targets.”

If DiMaggio’s interpretation is correct and SilverFish itself is Cozy Bear (APT29), this opens up the possibility that APT29 regularly draws on the services of cybercriminal groups such as EvilCorp and Conti/Trickbot -- or even that these groups are among the teams that Prodaft identified (Team 301, Team 302 etc.) as part of the SilverFish hierarchy. This is consistent with the US Treasury Department's finding that, as of 2017, "Yakubets was tasked to work on projects for the Russian state, to include acquiring confidential documents through cyber-enabled means and conducting cyber-enabled operations on its behalf."

The Conti/Trickbot modus operandi, discussed above, can also be incorporated into the image of Conti/Trickbot as a contract team under the APT29 umbrella. A plausible scenario might be something like this: Conti member “Professor” or “Stern” speaks with his contact in the SVR or FSB, who gives him guidance on what to look for in the group’s already-compromised victim servers. The SVR or FSB contact would enter that assignment into the “ticketing” system Prodaft described, crediting it to Conti’s team. “Professor” or “Stern” would go back and assign the task to team members.

If such a hypothetical scenario is correct, this would imply a different model for how APT29 is structured. Under this scenario, these criminal groups, likely working on contract, would spend at least some of their time carrying out assigned “tickets” or tasks as integral parts of the hierarchical and well-organized espionage operation that Prodaft outlined. (APT29 may have changed contractors since then, after Conti disbanded and EvilCorp actors have had to evade sanctions pressure). On Healey’s spectrum of state responsibility, such a relationship would probably qualify as “state-integrated.”

This is very different from the common image of APT29 as consisting solely of full-time employees of the SVR and/or FSB. This type of arrangement resembles the emerging picture of Chinese group APT41 as drawing on the services of financially motivated companies such as i-SOON, as the Natto Team has discussed previously.

Update June 2 2025: In late May 2025, The German Federal Criminal Police Office publicly identified Stern as Vitalii Nikolaevich Kovalev (also spelled Vitaly or Vitaliy Nikolayevich). US officials had unsealed a 2012 indictment of Kovalev in 2023, associating him with another Trickbot nickname, “Bentley,” that he apparently shared with fellow group member Maksim Galochkin.

Update June 21 2025: In an announcement issued 18 June 2025, Ukraine's National Police said the November 21 2023 takedown of LockerGoga/Ryuk/Dharma suspects had allowed them to identify an initial access broker involved in Ryuk ransomware activity. The Ukrainian authorities’ announcements said (they turned him over to the US on 18 June 2025. They said he had been charged in absentia by the US, was already on an FBI most-wanted list, is a foreign national [i.e. likely Russian], and is 33 years old [as of 2025, i.e. born 1991 or 1992], was arrested in April 2025 in Kyiv on US request, and was involved in Ryuk activity. A glance at all the Slavic-named people on the FBI’s Cyber Most Wanted List did not immediately yield any cybercriminal suspects with birthdates of 1991 or 1992.

Part 1 introduces the concept of hybrid ransomware: how ransomware attacks serve both financial and political motives and may play a role in Russia's ongoing "hybrid warfare" against the West. In part 2a we look at how Russian cybercriminals are willing to act as warriors for the Russian state against its enemies, particularly the United States. Part 2b shows that Russian cybercriminals are still vulnerable to prosecution and face tension between profit-making and their duty to the Russian motherland. Part 3 argues that, since at least 2016, Russian strategists have explored the use of ransomware to pressure adversary countries. Part 4a makes the case that Russian ransomware actors are “hybrid” in another way: criminals but also valuable IT talent with a fearsome reputation, to be coopted with carrots and sticks comparable to the treatment of common criminals. Part 4b argues that sometimes-puzzling Russian law enforcement patterns in recent years resemble less a desire to crack down on cybercriminals than an effort to use the threat of ransomware as a bargaining chip in pursuit of Russian strategic goals. “Ransom-War in Real Time, Case Study 1” focuses on the Conti/Trickbot and Evil Corp ransomware groups — both of which are known to cooperate with intelligence services — focusing on their real-time mechanisms of interaction with state officials. “Ransom-War in Real Time, Case Study 2” examines two disruptive ransomware events from 2019 that show signs of possible state involvement in targeting and timing. “Ransom-War and Russian Political Culture: Trust, Corruption, and Putin's Zero-Sum Sovereignty,” draws on recent Western government revelations about EvilCorp to explore how Russian ransomware actors and the Russian government use each other against the background of Russia’s low-trust, zero-sum political context. “Ransom-War in Real Time, Final Case Study: Tumultuous 2021” puts major ransomware operations of 2021 in the context of this political culture and international tensions of that year.

The group’s data has become public in numerous overlapping leaks. These include documents from summer and fall 2020, which Wired analyzed in an early-February 2022 report (https://www.wired.com/story/trickbot-malware-group-internal-messages/); a leak dated August 5 2021 by user “m1Geelka” [https://resources.prodaft.com/conti-ransomware-group-report]; data from Conti servers that the cybersecurity company Prodaft obtained in 2021 [https://resources.prodaft.com/conti-ransomware-group-report]; the famous “Conti-Leaks” made public soon after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and the “Trickbot leaks” that followed a few weeks later https://www.nisos.com/research/trickbot-trickleaks-data-analysis/). The Natto Team is unaware of any discrepancies between the various leaks that would indicate tampering.

According to Nisos, “Silver” also goes by the nickname “Buza.” On September 7 2023 the US indicted numerous Conti/Trickbot members, including Maksim Rudenskiy a.k.a. Buza. A US Treasury Department sanctions announcement from the same day identifies Maksim Rudenskiy as “a key member of the Trickbot group and the team lead for coders.”

“Professor” was “responsible for the whole technical process of securing a victim infection,” as Israel-based cybersecurity company Checkpoint described his role. “Professor” is clearly superior to “Mango”; in one March 16 2021 chat discovered by Kela, “Mango” reports that Professor gave the task of developing software “to extract databases containing contacts from our targets’ data.” Mango suggested adding features, such as checking for duplicates and emails’ validity. According to Kela, Mango (a.k.a. “khano”) “s a general manager providing support to stern, and assistance to the teams. As part of his activities, he was also looking for compromised network accesses for deploying ransomware.” In August 2022 the US State Department Rewards for Justice sought information on “professor (aka alter): ransomware negotiator.”

Many thanks to Jambul Tologonov of Trellix for providing the Russian originals of conversations dated July 14, 15 and 23, 2020 and for discussions of what the likely-misspelled word плился was supposed to be.

Target’s message — actually a burst of short messages — literally says “…тм уже паника /у всех / после трика / когда он плился / как не в себ / я.” [line breaks added]. The word плился could be a typo for злился — “was angry,” as the phrase злился как не в себя is a widely recognizable Russian phrase meaning “beside himself with anger.” If that were the case, Target’s message would read, “…everyone is already panicking over there, after Trick, when he was beside himself.” However, the fact that the verb is imperfective (he “was” mad rather than “got” mad), and the fact that the “п” key is far away from the “з” key on the Russian keyboard, call into question whether Target meant to write злился. Another possibility, given that the “a” key on Target’s keyboard appears to be sticky (he wrote тм instead of там), is that плился is a typo for палился: “was burned,” i.e. the Trickbot group or a person nicknamed “Trick” lost their cover or were unmasked. In that case, the message would mean, “…everyone is already panicking over there, after Trick got burned — they were beside themselves [with panic].” Update November 21 2024: evidence for this interpretation centering on the verb палиться (to be unmasked) is a 2012 forum posting by a cybercriminal who boasted that his nickname was непалевный = untraceable.

Media reports merely mention a 2014 spearphishing campaign by Russia’s GRU military hackers targeting Academi employees.

Activists were particularly interested in Blackwater at the time, amid ongoing court cases about the deaths of civilians in Iraq in 2007. Hacktivist Phineas Fisher had issued a manifesto in November 2019, calling on fellow hacktivists to breach organizations such as Blackwater. In July 2020, a report on Blackwater chief Erik Prince, based on the so-called “Bahamas Leaks,” appeared on the website of US-based investigations collective Unicorn Riot.

DDoSecrets characterizes itself as a nonpolitical “transparency collective” dedicated only to making secret information available to the public. Indeed, they have published leaked data from a variety of countries, suggesting they do not prefer one country over another. DDoSecrets administrator Emma Best makes some effort to vets the material for obvious disinformation and also restricts access to some sensitive data, making it available only to people Emma Best considers to be bona fide researchers. In addition, Emma Best warns users to watch for “malware, ulterior motives and altered or implanted data, or false flags/fake personas” in the leaks they publicize.

Despite these public-spirited gestures, however, DDoSecrets runs the risk of encouraging ransomware actors. On January 6 2021 they published data that threat actors using Russian ransomware families Snatch and Cl0p (Cl0p) had stolen from ten Western companies. They justified this by saying the data had already been released by the hackers and that wider distribution of it would be in the public interest. However, by publishing this material and making it available to DDoSecrets’ readership — people who self-identify as social-justice activists – this brings wider publicity for the ransomware actors, greater risk for the victims of their activity, and national security threats.

This is because the Snatch and Cl0p ransomware actors might themselves have been doing favors for the Russian government. The Snatch team, for example, has stolen national security-related data from US and German government contractors in the past, and it sometimes gives away data for free, suggesting its motives are less financial than political.

Note: On August 12 2024, 404 Media reported that DDoSecrets had been cofounded by Thomas White, who served five years in a US prison for running the Silk Road 2.0 online drug marketplace and for possessing child pornography. DDoSecrets promptly issued a statement saying “Thomas White exited DDoSecrets in April 2019 and has not been involved with the project since” and that Emma Best had been unaware of his exploitative activities until that time.

US and EU sanctions against Igor Chayka, the former General Prosecutor’s son, said he had helped plan and fund Russian FSB projects aiming to undermine the pro-Western government of Moldova. Thus, Maksim Yakubets was involved with people who played a role in Russian influence operations, i.e. Russian hybrid warfare, whether or not Yakubets himself was involved in those particular efforts.

The NCA report says, “Multiple other members of the Evil Corp group have their own ties with the Russian state. In particular, Yakubets’ father-in-law, Eduard Benderskiy, was a key enabler of Evil Corp’s state relationships.”

Recall that APT29 aka the “CozyBears” used to be attributed to the FSB before January 2018, when Dutch journalist Huib Modderkolk, citing Dutch intelligence service AIVD, attributed Cozy Bear activity to Russia’s SVR. The Estonian intelligence service attributes CozyBear activity to both the SVR and the FSB. DiMaggio’s observation that Yakubets has ties with the FSB but that EvilCorp has ties with SilverFish/SVR lends weight to the idea that APT29 works for both of those agencies.

"Skeptics of the Natto Team’s “hybrid ransomware” thesis have raised numerous important questions: Can Russian cybercriminals seriously be receiving direct government tasking? If so, how do they communicate? Or are they improvising based on more diffuse “patriotic entrepreneurialism”?"

These activities were developed and successfully deployed the day before the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008 and were first tested on the Estonians a year earlier. This was probably Russia's first successful Gray zone cyber operations.

The GRU planned well a head time, developing asset lists and websites to help disseminate how to attack the list. They made it easy enough for everyday citizens to help them develop the battlefield prior to the invasion. There is no doubt that they have continued to develop and refine those capabilities. Great work putting together this series looking forward to more installemnts. Cheers!