Ransom-War, Part 2a: Extortion Entrepreneurs and Their Patriotic Obligations

Russian ransomware actors and other cybercriminals are business people first, but they have to do their duty to the motherland

Russian cybercriminals like to talk: in personal communications, postings on underground discussion forums or social media pages, in the websites where they name and shame victims, in ransomware negotiations, and in media interviews. Analyzing their publicly available statements, we see they often portray themselves as warriors for the Russian state against its enemies. In line with the messaging of Russian media and officials, cybercriminals often focus their ire on the “collective West,” especially Americans and other “Anglo-Saxons.” Particularly after someone in the US has unmasked or indicted Russian cybercriminals or taken down their operations, they call for retribution against the United States. They take a keen interest in US politics and sometimes appear to take sides in US partisan conflicts. They are willing to work for the Russian government and sometimes make business decisions that align with Russian strategic interests. The early weeks of Russia’s war on Ukraine saw Russian cybercriminals rallying to the defense of the motherland. Doing their patriotic duty sometimes came into tension with their business success. But they realized the Russian government holds the upper hand and can compel them to help.

This is the first half of part 2 of the Ransom-War series. Part 1 reviewed other authors’ findings about the relationship between cybercriminals and the state and introduced the series. The second half of part 2 looks at the tensions Russian cybercriminals experienced between profit-making and their patriotic duty. Parts 3-4 look at the state-criminal relationship from the state’s point of view. Part 3 argues that, since at least 2016, Russian strategists have explored the use of ransomware to pressure adversary countries. Part 4a makes the case that Russian ransomware actors are “hybrid” in another way: criminals but also valuable IT talent with a fearsome reputation, to be coopted with carrots and sticks comparable to the treatment of common criminals. Part 4b argues that sometimes-puzzling Russian law enforcement patterns in recent years resemble less a desire to crack down on cybercriminals than an effort to use the threat of ransomware as a bargaining chip in pursuit of Russian strategic goals. Part 5 will explore criminal/intelligence cooperation in specific ransomware operations.

Hackers At War

Russian cybercriminals have made statements suggesting they see themselves as patriots and warriors for the Russian state against its enemies.

But First, A Note on Sources: What to Believe?

Naturally, claims by Russian cybercriminals need to be approached with caution. This report draws on the words of Russian hackers as seen in leaked communications, postings on underground discussion forums or social media pages, statements reportedly made in courts of law, and interviews with Russian or Western journalists.

Caveat 1: Different Messages for Different Audiences

In each of these settings, the hackers likely have in mind a particular audience. They say different things to different audiences, depending on their aim – whether to drum up business, recruit new members, or avoid legal exposure – and what they deem politically acceptable. Leaked direct messages likely provide the best reflection of their actual thoughts. As for their statements on underground forums, the hackers likely feel somewhat free to speak their minds, as they are addressing a like-minded community, but they still likely seek to impress potential clients, intimidate competitors, and avoid the attention of law enforcement and researchers who might lurk on the forums. In more public and official settings, such as interviews and court appearances, the hackers likely feel most pressure to fine-tune their message.

Interviews: Cultivating a “Strictly Business” Image

As noted, Russian hackers likely vary their message depending on the setting, and this shows up most clearly in their interviews, where they can tailor their words to their intended audience.

One main source of hacker interviews are the YouTube and Telegram channels of Russian cyber-journalist RussianOSINT. Carried out in the Russian language and featuring sensationalist visuals, these likely appeal mainly to fellow Russian-speaking cybercriminals or would-be hackers, as well as law enforcement and cybersecurity researchers who understand the language.

Another main source of Russian hacker interviews is The Record, a publication of the US-based cybersecurity firm Recorded Future. Conducted in English but with less sensationalist fanfare, these interviews likely attract a more global but more cybersecurity-focused audience. Most of these interviews were conducted by Dmitry Smilyanets, a former Russian hacker himself who has served time in a US prison. When Smilyanets reached out to a hacker for an interview, the potential interviewee likely viewed Smilyanets with a mixture of trust – as someone who “speaks their language,” both literally and figuratively – but also distrust, as someone who cooperated with US prosecutors and now works for a US company researching Russian cyber threats. Even more perplexing, Dmitry’s own father, a famous Moscow lawyer, has reportedly been defending one of the REvil ransomware suspects in Russian court. Russian hackers may wonder where Smilyanets’ loyalties lie and how much to reveal in their interviews with him.

In most media interviews, Russian hackers portray their profession as a glamorous and lucrative lifestyle. They often claim to make decisions strictly on business rather than ideological grounds. Similarly, in statements after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the LockBit group claimed, “For us it is just business and we are all apolitical,” though group members’ subsequent actions would call this into question. Other groups made similar statements in 2021 after their attacks led to undue scrutiny; DarkSide and REvil actors claimed to have nothing to do with politics.

Or Boasting of State Ties….But Only While Expedient

In contrast, on other occasions hackers have deliberately exaggerated their connection with the Russian state or other influential organizations, if it seemed likely to help them evade criminal responsibility.

“Fancy Bear” Pavel Sitnikov:

Voluble Russian hacker Pavel Sitnikov, who sells malware and stolen data on the dark web, has sometimes claimed to be affiliated with the “Fancy Bear” Russian military hacker group, also known as APT28. A mish-mash of allusions to security services and variations on “APT28” appear in some of his social media profiles.

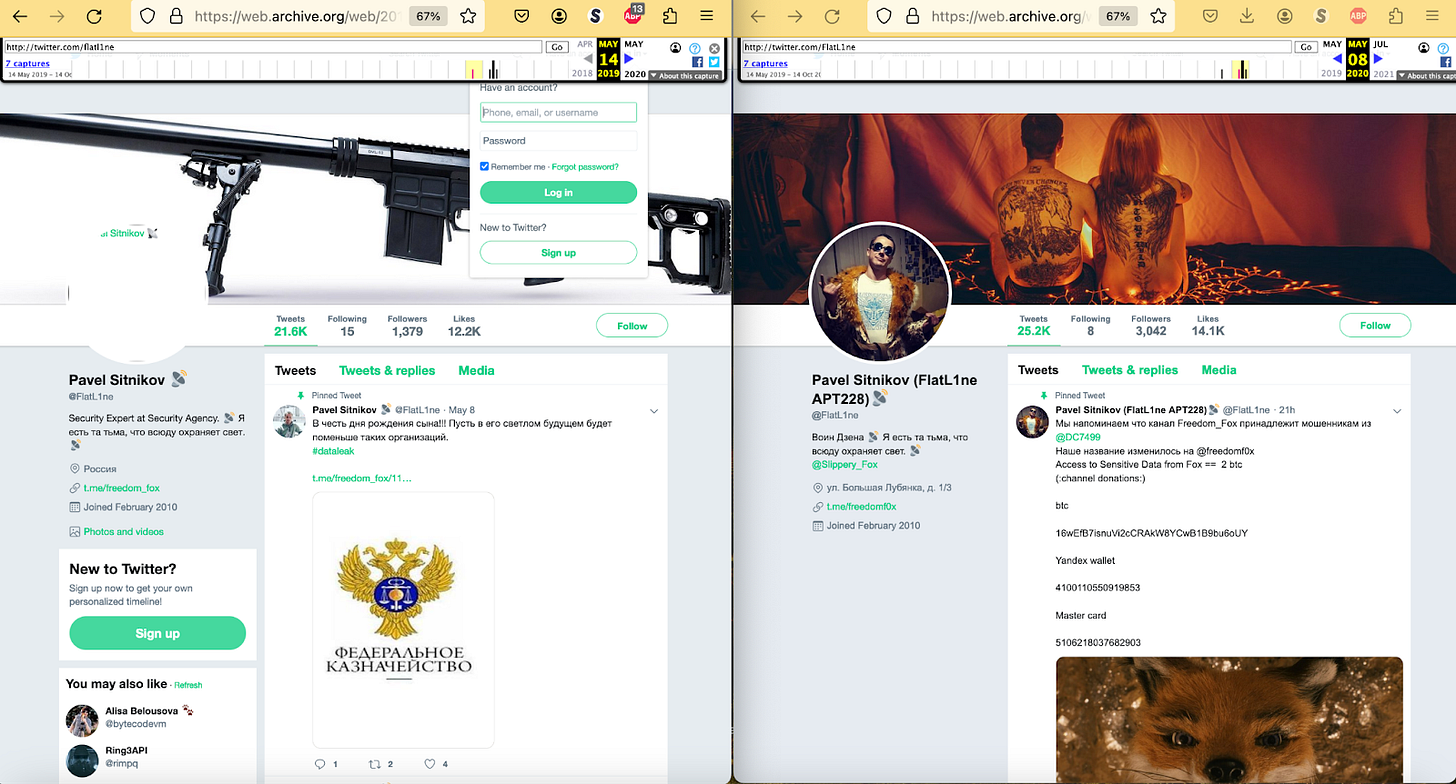

Two cached screenshots from Pavel Sitnikov’s Twitter account. The page cached on May 14 2019 (left) describes him as “Security Expert at Security Agency.” The one cached on May 8 2020 (right) claims his address is ulitsa Bolshaya Lubyanka ⅓, which is the address of the Russian FSB.

Sitnikov claimed in a 2021 interview with Recorded Future that he had taken on this false identity simply as a lark, during a conference back in 2016.

We decided that at the conference I would be presented as ‘the one’ from Fancy Bear, who hacked Hillary Clinton. I agreed, it was fun. Then I changed all my profiles on forums and social networks, so as to appear affiliated with APT28..... other foreign intelligence services started to believe in this...to deceive practically all of the intelligence communities in the world was absolutely amazing.

However, in the same interview Sitnikov tried to explain away evidence that he really had worked for a Russian contractor that made hacking tools for the Russian state.

“Spam King” Pyotr Levashov

Pyotr Levashov (a.k.a. Severa), a “spam king” who also sold stolen credit cards, liked to make April Fool’s jokes. On April 1 2012 he said he would head up a Microsoft cybercrime team. On April 1 2013 he claimed to be creating a new team within the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) to counter US cyber-warfare. “I’ve been instructed not only to lead [this unit], but to form its main staff,” the 2013 post read. “A college degree in computer science is a plus... Having finished at a military academy or completed Russian military service is also a plus. The Motherland raised us, giving us our educations. Now our time has come to serve Russia.” Analysts suspect he may have fabricated a connection to the FSB as an April Fool’s joke, though his posting may actually have attracted some potential FSB recruits.

In 2017 Levashov was arrested in Spain. In an effort to evade extradition to the US, he and his lawyer claimed he had worked for Russian President Putin’s party and would therefore be tortured or driven to suicide as a political prisoner if he were sent to a US prison. He ended up being extradited to the US anyway, pled guilty, and in 2021 received a sentence of time served and supervised release. That year, now at liberty and looking for work, he gave an interview to Time magazine. There Levashov changed his story about his ties to the Russian state; he claimed his words in 2017 had been lies to win sympathy from the Spanish judge and to make the U.S. charges against him seem political. “That was all a big lie...I never worked for Putin or anything like that.”

Lurk Group Member Konstantin Kozlovsky

As mentioned in our previous posting, Lurk crime group member Konstantin Kozlovsky made multiple appeals to court authorities as they repeatedly considered extensions of his pre-trial detention. In these appeals he claimed to have been recruited by supposed double-agents in the FSB to develop malware to hack the US Democratic National Committee and to breach presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s email. Successive appeals have added more names to the list of supposed traitors whom Kozlovsky blames for his criminal activity.

Caveat 2: Affiliates vs. Ransomware Bosses

As a second caveat, statements made on ransomware-as-a-service data-leak websites or during ransomware negotiations are sometimes written not by the crime group leadership but by the affiliates who rent the use of the ransomware service. For example, we saw previously that the hacker nicknamed “Wazawaka” claims to have been the affiliate nicknamed UNC1756 who used the Conti group’s malware to cripple the Costa Rica government in 2022, then used the Conti website to mock US President Joe Biden.

Depending on the terms of the affiliate agreement, ransomware group leaders might carry out ransom negotiations with victims, but the affiliate might be able to suggest what to say. A New York Times reporter obtained a chat from a DarkSide group affiliate panel that showed this relationship. Affiliates do have some limits; they are supposed to adhere to any guidelines the bosses might make -- such as not targeting Russian-speakers and sometimes refraining from targeting certain sectors. Regardless of whether the statements on a ransomware group’s website come from the group’s leaders or from an affiliate, in either case they show opinions that exist within the hacker community.

Russian Hackers Express Deep Patriotism

Russian hackers often express patriotic loyalty to the Russian motherland. The sentiments do not appear to have been just empty rhetoric. As we saw, hacker Mikhail Matveev (Wazawaka)’s current Twitter bio identifies him as a “Russian security artist,” embracing Putin’s smirking characterization of Russian hackers as patriotic “artists.”

Investigators with firsthand knowledge of Russian cybercriminals have found a mix of financial and patriotic motives. Simon Williams, formerly of the London Metropolitan Police and the UK National Crime Agency and now of US-based cybersecurity firm Intel471, has spoken with half a dozen Russian and Ukrainian threat actors over the years. Both groups said their turn to crime was partly motivated by the inability to use their skills in legitimate business, because setting up such a business requires paying people off. However, the two countries’ hackers differed in that the Ukrainians said they hacked simply in order to make money, while Russian actors told Williams that making money was a large part of their motivation, but deep patriotism also played a role. This has likely changed since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022; patriotism likely plays a greater role in motivating Ukrainian hackers as well (personal communication, April 9 2024).

“National pride is something I have seen interwoven into the [Russian] underground community,” Richard LaTulip, a former US Secret Service Cyber Intelligence agent who interacted with Russian cybercriminals as part of undercover operations, said in a January 2021 interview with Dmitriy Smilyanets for The Record. “For example, when online one can sense an “Us-vs-Them” ideology.....The way some criminal actors write—in the online posts, links to articles—one can feel at times the “us” is them and their country and the “them” means most other countries. I gather from this information that to a degree they believe they are serving their country.”

Reporting on Dmitriy Smilyanets himself over the years suggests a mix of demonstrative patriotism, genuine love of country, and an increasingly dangerous nationalism among hackers in today’s Russia. In 2012 Smilyanets praised Putin and expressed pride in Russia. At that time, he was building a Russian e-sports team in an effort to make a legal living as “a way out of the hacking world,” according to the Wall Street Journal. However, the US Secret Service caught up with him during one of his foreign trips, and he served time in a US prison before joining Recorded Future. In contrast with the hacker culture of his youth, he thinks today’s Russian hackers are deadly serious. In a 2023 interview he said, “I can't hate Russia. I was born there…But now what I see is different Russia, angry, evil. That scares me.” Asked at a 2023 US conference presentation about the mindset of today’s Russian ransomware actors, he said, “I think they got involved into this propaganda and war machine and now.... these hackers let loose so they see no boundaries ... including attacking hospitals....These are cyber terrorists and we have to treat them accordingly” (minute 46:31ff of the presentation video).

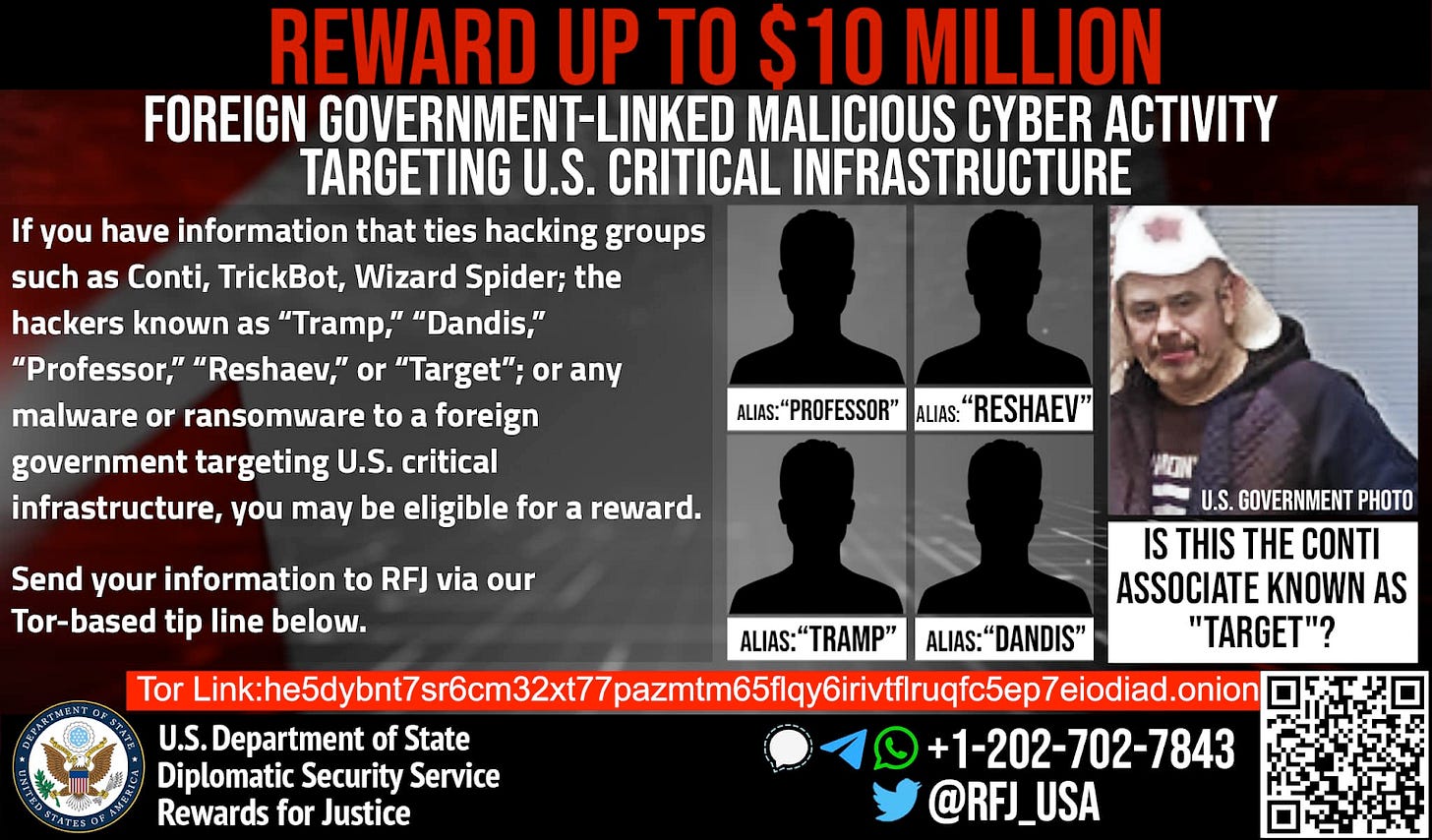

Russian hackers are also steeped in a culture that glorifies military heroes. One example is a photo appearing on an August 11 2022 US State Department Rewards for Justice program poster. The photo – depicting a man the US suspects of being Conti group member “Target” – shows the man wearing a white budyonovka (буденовка), an ear-hugging cap decorated with a red star. This kind of cap, currently advertised as sauna-wear, imitates the wool caps that early Soviet soldiers wore; it symbolizes Soviet military gallantry.

US State Department Rewards for Justice Poster, August 11, 2024 https://rewardsforjustice.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CONTI-EN-1.jpg

Hatred of Russia’s Enemies

Hackers often express hatred and resentment of Russia’s enemies, especially of Americans and other “Anglo-Saxons.”

A list of email addresses related to the Conti group includes entries like “fuckusa,” “fuckusahahaha,” and “pravdazanami”; the latter phrase in Russian means “the truth is on our side.”

On May 9 2022, an online persona nicknamed “Sheriff” posted on an underground forum, offering to pay $50,000-$150,000 for login credentials for vpn1.colpipe.com, the website of the same Colonial Pipeline that a Russian ransomware attack had paralyzed exactly one year before. “Sheriff” commented: “Love seeing these dirty ... americans scramble for supplies” [sic]. Researchers have identified “Sheriff” as Saint Petersburg resident Aleksandr Sikerin, an affiliate of the REvil ransomware group.

Pavel Sitnikov, the voluble hacker discussed above, said in a 2020 interview with a Russian business periodical, “we want to destabilize America.

You know, destroy it, just as they want to destroy us.” (hxxps://expert[.]ru/expert/2020/39/oni-ne-pomnyat-nas-horoshih-pust-ne-zabudut-nas-plohih/)In a 2019 report, researchers from cybersecurity firms McAfee and Coveware analyzed a Ryuk ransomware operation. The malware is related to Trickbot and Conti, and Ryuk actors sometimes worked with the Conti group. The 2019 report found that one of the operators used a Soviet cultural reference: “explaining their motives, the attackers told their victim: ‘à la guerre comme à la guerre’.” “War is war.” The researchers identified this French-language expression as one that Russian revolutionary leader Vladimir Lenin had used in his writings. (The phrase in Russian, на войне как на войне, is also the title of a patriotic Soviet movie and memoir about World War II-era heroes). By using Lenin’s phrase, the Ryuk ransomware actors were apparently implying that their crimes constituted a war or revolution against rich countries. The researchers noted that this aligns with their finding that “’the capitalistic West versus the poor East’ was a motif in cybercrime attacks stemming from some post-Soviet states.”

In other examples as well, Russian cybercriminals express their hostility to Anglo-Saxons in terms of resentment against rich countries. A hacker nicknamed “Kerasid,” apparently linked with both REvil and Conti groups, was interviewed by Australian media in 2023. He said, “Australians are the most stupidest humans alive and they have a lot of money for no reason, a lot of money and no sense at all....I loved American targets because I am not a fan of the Americans...Companies in the States have quiet [sic] a lot of money. I loved seeing them suffer."

Undermining Western Hegemony:

Some Russian hackers target other countries simply because of their association with the United States. As mentioned above, Wazawaka claimed to have been the entity calling itself “UNC1765,” who crippled Costa Rica in mid-2022. UNC1756 made statements denigrating Costa Rica’s closeness to the United States and calling for an uprising in Costa Rica. He may have been trying to take advantage of a real political crisis taking place that year in Costa Rica, where “an unusually low turnout ... reflect[ed] the lack of enthusiasm Costa Ricans had for the candidates.” But UNC1756 did not bother to mention some real scandals involving the incoming president, including allegations of sexual harassment and an “illegal financing structure.” Instead, UNC1756 focused on the United States. He called Biden a terrorist and said, “the USA is a cancer on the body of the earth…we hope that soon in the usa power will change and Biden will die.” That is, he was not really interested in Costa Rica for itself but as a weak link in the United States’ sphere of influence.

In a 2022 interview with The Record, fellow hacker Pavel Sitnikov provided a similar assessment, that the attack on Costa Rica was an event in a larger geopolitical struggle against US influence in the Western hemisphere. “Conti is supervised by serious dudes in power. An act of vandalism with Costa Rica is again a cover for important events in the world’s redistribution of spheres of influence! All of this is right out of the ‘Conducting Sabotage Activities’ textbook ; )”

In an example of hostility toward powerful Western institutions for their support for Ukraine, on June 14, 2023, members of the REvil ransomware group joined with pro-Russian hacktivist groups KillNet and Anonymous Sudan, posting on Telegram a threat to target the European and US financial system, “following the formula of ‘no money - no weapons - no Kyiv regime’," according to Trustwave.

Retribution Against Those Who Unmask and Prosecute Them

Many Russian cybercriminals claim they are taking retribution against Americans and their allies for catching, unmasking, sanctioning or indicting them.

Members of the GandCrab group in 2018 engaged in what South Korean cybersecurity company AhnLabs called a “war” that included taunting the company and releasing what it said was a zero-day exploit for cracking AhnLabs tools.

On October 26, 2020 – perhaps in revenge for US operations that partially disabled Trickbot/Conti infrastructure – Conti group member “Target” wrote, “Fuck the clinics in the USA this week. There will be panic. 428 hospitals.” US officials scrambled to warn of an “imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers.” However, according to US researcher Brian Krebs, attacks on healthcare organizations did not appear to spike that week; they appeared to remain at about the same (outrageously high) level as usual – roughly one per day.

In the January 2022 video described in an earlier Natto Thoughts posting, Mikhail Matveev (Wazawaka) ranted against Brian Krebs, who had unmasked him. Matveev slurred, “I declare war on the USA!”

In late April 2022 a person claiming to be the REvil actor “Sheriff” told journalists, “i hate americans and i also hate researchers.” Individuals associated with Sheriff also threatened cybersecurity researchers Dissent-Doe and pancak3 that month.

Calling for Redoubling Attacks on Western Countries

Russian ransomware actors not only rail against Western governments that have taken action against them, but also sometimes call for retribution through new attacks on those countries. They unconvincingly claim that they had been restraining themselves from attacking critical infrastructure but say they will now abandon that supposed restraint.

In mid-2021, after the blowback from the May 2021 Colonial Pipeline hack had caused the administrators of underground forums to limit discussion of ransomware, REvil group leaders quickly resumed attacks on Western critical infrastructure: this time, the food sector. A Revil affiliate targeted Brazil-based meatpacker JBS on the eve of the US Memorial Day holiday, raising fears of empty American barbecue grills on that day. A purported Revil hacker claimed in a June 4 2021 interview (hxxps://t[.]me/Russian_OSINT/791) that he had really been trying to avoid hitting US targets. He claimed he thought he was attacking Brazil. Referring to the Colonial Pipeline hack, he said, “With the recent events in the fuel biz, we tried to stay away from the U.S, just like we don’t target the critical infrastructure...The attack was against the company in Brazil, but it was the U.S. that got mad.” Since the US made such a fuss about it, the purported REvil spokesman claimed, he was declaring open season on US targets: “Since there’s no point in avoiding the US targets anymore, we have lifted all the restrictions....From now on, every entity in this country can be targeted...access to US companies will be sold for a song, and we’ll offer preferential terms to our affiliates.”

After US and other law enforcement took over websites of the AlphV group and issued a decryption tool in December 2023, a posting on the AlphV site said, “Because of their actions we are introducing new rules. Actually, we are removing ALL rules, except one: do not touch the CIS [i.e. former Soviet countries]. You can now block hospitals, nuclear power stations, whatever you want and whereever you want.” They listed two more provisions to encourage affiliates to target US critical infrastructure: 1) they said affiliates could keep 90% of the ransom payment, rather than the more usual 80%, and 2) they said they would not allow victim companies to bargain them down to a lower ransom.

Keen Partisan Interest in Western Political Divisions

Russian cybercriminals love to read about themselves in the global media, even as they sometimes issue rebuttals against what they perceive as incorrect coverage. After researcher Jon DiMaggio published a three-part series on the LockBit group, a LockBit actor boasted, “no matter what Johnny says, I still love him, he is my most devoted fan and follows every sneeze, turning any sneeze into a huge sensation, a real journalist.” (On May 7 2024, US, UK and Australian officials publicly identified LockBit group leader LockBitSupp as Dmitry Yuryevich Khoroshev. A US court indicted him in absentia. Researcher Jon DiMaggio posted additional information about Khoroshev and “a note to my old nemesis, LockBitSupp,” telling him, “It’s time to move on.” Researcher Brian Krebs, who corresponded with the LockBitSupp on the Tox instant messenger, said LockBitSupp denied being Khoroshev but noted that LockBitSupp “has been known to be flexible with the truth.” Regardless, Khoroshev is beyond the reach of foreign law enforcement).

Russian hackers also follow global news, particularly in the United States.

In some cases, Russian ransomware actors borrow the names of particular actors in the US political arena, showing their interest in US politics.

One of the Trickbot/Conti group members chose the nickname “Tramp,” which is how Russians spell the name “Trump” (Трамп). (There is no short “u” sound in Russian).

Another group member, Vadym Valiakhmetov, chose “Weldon” as one of his nicknames, possibly a reference to former US Congressman Curt Weldon, whose name has appeared in the media over the years in connection with his ties to Russia.

In some cases, they threaten to release politically sensitive stolen information, purportedly to extort a bigger ransom.

In May 2020, after breaking into the the Grubman, Shire, Meiselas and Sacks law firm, REvil operators posted sample data relating to one of that firm’s clients, the singer Lady Gaga. They added, “The next person we'll be publishing is Donald Trump. There's an election race going on, and we found a ton of dirty laundry on time. Mr. Trump, if you want to stay president, poke a sharp stick at the guys, otherwise you may forget this ambition forever. And to you voters, we can let you know that after such a publication, you certainly don't want to see him as president....” Soon they published the supposedly incriminating data -- an unremarkable set of texts that happened to include the string “trump.” But the threat actors implied that Trump’s campaign should buy it, because otherwise candidate Biden’s team would buy it and use it against Trump.

LockBit gang spokesperson LockBitSupp, after bricking up the systems of Fulton County, Georgia in February 2024, also cited a sensitive US election. After the US FBI and the UK’s National Crime Agency seized LockBit’s victim-shaming blog, LockBitSupp published what Brian Krebs described as a “lengthy, rambling letter” on February 24. In it, LockBitSupp claimed to have restored its websites and again threatened to leak Fulton County data unless the county paid a ransom. “The FBI decided to hack now for one reason only because they didn’t want to leak information fultoncountyga.gov,” LockBitSupp wrote. “The stolen documents contain a lot of interesting things and Donald Trump’s court cases that could affect the upcoming US election.” This occurred shortly after Donald Trump and other defendants had called for the judge to be disqualified due to a personal relationship. This operation resembles an incident the Natto Team mentioned earlier, when the Babuk group in April 2021 released Washington DC police material related to the insurrection of January 6.

In some cases, Russian ransomware actors appear to be trying to influence or exacerbate those US conflicts:

The REvil outburst after the US response to the June 2021 JBS hack showed deep familiarity with US policy developments: “We don’t want to play politics, but seeing as we are being dragged into it — well, alright then...Even if the U.S. government passes the bill prohibiting ransom payments or puts us on the terrorist list, that’s not going to affect our operations. Quite the contrary, access to US companies will be sold for a song, and we’ll offer preferential terms to our affiliates.” They were referring to ongoing US government discussions of banning ransomware payments and to reports from June 3 2021 that the US Justice Department’s new anti-ransomware task force would investigate ransomware conspiracies with as much urgency as it treated terrorist conspiracies.

We already saw Wazawaka claiming to be the entity named UNC1756, who crippled the entire country of Costa Rica in 2021 and taunted US President Biden. Earlier that year, his Babuk group’s introductory message had insulted two other politically sensitive groups; it explicitly authorized its affiliates to target “foundations who help LGBT and BLM,” referring to lesbian, gay, bisexual and transsexual people and to the Black Lives Matter racial justice organization, respectively. In this way Wazawaka was echoing Russian state media, which portrays LGBT and Black Lives Matter activists unsympathetically.

More recently a Russia-based group adopted a name that is racially charged in the United States. The group, calling itself “Cyberniggers,” proudly flaunts its racism. It also targets major US companies with military significance.

Putting Their Money Where Their Mouth Is

Russian cybercriminals sometimes take Russian strategic interests into account in their business decisions. We saw how Wazawaka leaked data stolen from the Washington DC Metropolitan Police Department even though he expected no ransom from them, an example of sacrificing profits for the good of the Motherland. Other ransomware actors sometimes act similarly.

For years, Russian hackers have shown their patriotism through providing discounts for favored countries and incentives to attack less-favored ones.

When Russia seized Crimea and installed separatists in eastern Ukraine in 2014, carder Pyotr Levashov offered 30% discounts to people who would send spam to users in Ukraine, the US, EU countries and ”others who imposed sanctions” on Russia.

In 2018, threat actor GandCrab (a predecessor to the REvil group) vowed to make a humanitarian gesture to residents of Russia’s war-torn ally Syria; if its ransomware had bricked up any of their systems, GandCrab would provide decryption keys. However, GandCrab declared they would never release keys to victims in certain other countries, as “we need to continue punitive proceedings against certain countries.” Accenture iDefense observed that GandCrab’s targeting in October 2018 included entities in Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands — countries that had actively investigated and denounced chemical attacks by the Syrian government against civilians. The GandCrab actor was identifying themselves with Russia’s strategic priority of defending Syria.

Hacker Pavel Sitnikov, in a 2020 interview with a Russian business magazine, sketched out his vision of an ideal world for hackers: “where we will feel comfortable, and the government will come and ask us nicely, with a cookie, 'Here you go, guys. Now we need you to destroy another country...'” To this, in Sitnikov’s imagined world, the hackers would answer, “'No question about it! Let's do it!!'" Sitnikov has boasted of breaching the US National Security Agency (NSA) and other US entities to help "destabilize America... destroy it, just as they want to destroy us." (hxxps://expert[.]ru/expert/2020/39/oni-ne-pomnyat-nas-horoshih-pust-ne-zabudut-nas-plohih/)

The new CyberNigger group targets companies with military significance in the US and other NATO countries and usually asks very low prices for sensitive information. As cybersecurity firm SocRadar notes, “the offer to sell access to DARPA [US defense research agency] files for $500 raises questions about the authenticity and motivations behind such a seemingly undervalued proposition. In a tweet, they also stated that they sold sensitive US-based data for $4000...” SocRadar’s observation suggests that either the information is not genuine or that CyberNigger’s leaks were intended more for spying on or harming US national-security interests than for making money.

Ransomware actors have sometimes explicitly threatened to send the data to the Russian FSB or other intelligence agencies, flaunting their value as a source of intelligence

In 2021, the REvil ransomware actors breached US nuclear weapons contractor Sol Oriens and threatened to leak the data “to military angencies (sic) of our choise (sic)." Also in 2021, unknown hackers breached Spanish cloud computing company Everis, which holds NATO information. In a note to transparency group DDOSecrets they wrote, “I hope they appreciate we just deleted all of Everis’ garbage instead of backdooring it or dropping it in the FSB securedrop,” referring to Russia’s Federal Security Service.

That same year, the Babuk gang threatened to leak data of the PDI Group, a US military supplier, and posted purported sample data. They wrote, “The publication of this information may lead to problems with the law and cause concern to customers. In addition, given the state of international politics, the information may be of interest to countries such as Russia and China. We are ready to delete these files and help with solving security problems” as long as the victim paid ransom.

On December 3, 2023 user “Comradbinski” reportedly posted on an underground discussion forum, “Today cyberniggers breached into the Colonial Pipeline, as well as some other companies and have stolen 200GB worth of data and files. (Via a vendor that only works with Colonial).” Listing two dozen pipeline companies, the author concluded, “To the gov spies among us! This is your chance to gain critical intel!” Although this particular ad says, “Offers under 50k USD won’t be responded!” normally the CyberNiggers group offers their data for surprisingly low prices, according to SocRadar.

Some ransomware actors’ statements appear to align with Russian foreign policy positions

Natto Thoughts posting Too Many Toads cites evidence of the closeness of Conti leaders to the Russian government. After Russia invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the Conti group promptly issued a declaration of support for Russia. But within hours, it had tweaked its wording. Its first statement read:

The Conti Team is officially announcing a full support of Russian government. If any body will decide to organize a cyberattack or any war activities against Russia, we are going to use our all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy.

A few hours later, the Conti leadership replaced this with a slightly softer statement:

As a response to Western warmongering and American threats to use cyber warfare against the citizens of Russian Federation, the Conti Team is officially announcing that we will use our full capacity to deliver retaliatory measures in case the Western warmongers attempt to target critical infrastructure in Russia or any Russian-speaking region of the world. We do not ally with any government and we condemn the ongoing war. However, since the West is known to wage its wars primarily by targeting civilians, we will use our resources in order to strike back if the well being and safety of peaceful citizens will be at stake due to American cyber aggression.

Analysts try to explain this change in terms of the Conti leadership realizing their initial statement “might possibly backfire” or as a concession to Ukrainian members of Conti. Conti’s revised message, referring to people undertaking a cyberwar against Russia, did have some grounding in real events: the amorphous hacking collective Anonymous had promptly declared cyberwar against Russia on February 24 and taken down the website of the Russian propaganda network RT.

However, the Natto Team also assesses that the new statement sounds like something written by lawyers. Note that the message changed from threatening to strike any adversary’s critical infrastructure to claiming Western countries would strike Russian critical infrastructure. They switched the focus to “Western warmongers,” who they implied would target Russian civilians. As previous Natto Thoughts postings noted, Conti leaders had contacts in the Russian government and had even discussed setting up a government relations unit. The prompt revision may have reflected pressure on Conti from government officials to conform to Russian state messaging by portraying Russia as a victim. Russian officials and Kremlin-friendly media around that time were accusing the “Anglo-Saxon” US and UK as “warmongers” (поджигатели войны).

Expressing Willingness to Work for the Russian Government

Russian cybercriminals not only make business decisions to benefit the Russian state, but also express willingness to work directly for the Russian government.

Zarya, a Russian hacktivist entity formerly associated with Killnet and likely also affiliated with Russian military-supported hacktivist group Xaknet, claimed to have breached a Canadian gas distribution facility in February 2023 on orders from Russia’s Federal Security Service, journalist Kim Zetter has reported, citing leaked US military intelligence documents.

As mentioned above, Pyotr Levashov, the carder, claimed in 2013 that he was creating an FSB team to counter US cyber-warfare: “The Motherland raised us, giving us our educations. Now our time has come to serve Russia.” Although Levashov may well have been making an April Fool’s Day joke, Recorded Future notes that the posting “did elicit some lively conversation on the forums, including…from individuals who appeared to be taking the post seriously and indicated an interest in working for the new organization. This April Fools joke could have easily helped the Russian intelligence services to identify potential recruits among the threat actors who took the post seriously.” Furthermore, Levashov’s patriotic call-to-arms was consistent with past statements. As independent Russian media outlet Meduza wrote, in the mid-2000s Levashov frequently urged other hackers to perform patriotic hacking against Muslim extremists, and in 2012 he allegedly circulated spam emails portraying opposition presidential candidate Mikhail Prokhorov as a pedophile.

Case Study: Conti Carrying Out Tasks for Government Entities

As mentioned in previous Natto Thoughts reports, leaked Conti group discussions show the group leaders openly discussed carrying out tasks for Russian government contacts. As mentioned in “Too Many Toads”, and Ransom-War Part 1, a report by Trellix pulls together abundant evidence of Conti members’ ties with Russian government agencies, and the Natto Team used the Russian-language screenshots to draw out additional insights to enrich Trellix’ findings. Main points include the following:

Group members suspected that Conti group leader “Stern” had ties with the FSB or other agencies and “in service to Pu,” referring to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and that these connections helped Conti escape the Russian law enforcement crackdown of late 2021 and early 2022.1

Conti member “Target,” who acted as a government liaison, appeared to indicate that some of their assignments came from the Saint Petersburg branch of the FSB.

Member “Professor” said he was doing paid work for a foreign-intelligence service, likely Russia’s SVR. This appeared to include providing lists — likely of compromised computer systems — to the SVR hacker team Cozy Bears (a.k.a. APT29).

In addition to paid work, Conti leader Stern feels the need to do unpaid volunteer work, as if they were members of the Scout-like Soviet Young Pioneer organization.

As of 2020, Conti members took care not to accidentally harm anyone in Russia and also appeared to have been told to avoid Chinese targets as well, in alignment with Russian strategic interests at the time.

Conti group members worked with the Maze group to breach systems at US military contractor Academi (formerly Blackwater) and other military targets.

In addition, the Russian-language screenshots in the Trellix report cast further light on Conti group members’ actions.

On July 20, 2020, group members discussed the operataion against US military contractor Academi. As mentioned in Natto Thoughts’ “Ransom-War, Part 1,” they said “Target” planned to set up a whole office “for government topics” (под гос темы). An office “for government topics” could refer to an office for liaison with Russian government agencies on operations of interest to the Russian government, or to an office dedicated to targeting foreign governments. Israel-based cybersecurity firm Kela interprets it as targeting foreign governments. Actually these two interpretations are compatible, as evidenced by Kela’s further discussion of how “Target” envisioned such a team. Kela writes,

The group was supposed to research documents stolen from already compromised victims to define possible interesting government targets. He offered identifying all counterparties by their payments and correspondence and dividing them by priority. The main department will be preparing the attacks and compromising networks. target stated that the current work-scheme does not have consistency and control over the US public sector, and if this mission is important, they ought to build a specific system. Since the conversation took place in 2020, when Conti was not a well-established operation, it is not clear if the plan was performed.

The phrase “control over the US public sector” likely refers to visibility into that sector’s workings; the Russian word контроль broadly refers to monitoring. Kela did not provide a Russian original for the word “counterparties,” but it likely refers to Russian government clients who pay for Conti operations against US government entities.

Target’s planned strategy is a perfect model of a hybrid ransomware operation, which draws from the results of the criminals’ financially motivated operations to benefit the government’s strategic interests. This is how FSB officials worked with Russian cybercriminals to obtain intelligence from a 2014 hack of Yahoo, as detailed in a 2017 US indictment. Indeed, in 2020 this approach appears to have been already at play with the Conti group, judging from another quote from the same July 20 conversation. “Professor” said that contacts in a foreign-intelligence service (по внешке) paid him for tasks. Minutes later in the same chat, he said the “Cozy Bears” (кози медведи) – referring to SVR-linked state hacker group Cozy Bear – were “going through the list,” likely referring to lists of compromised computer systems, from which the SVR personnel could select entities for further targeting.

In the same July 20, 2020 conversation, Professor said his paying contacts “really want COVID-related [things] right now.” He likely had in mind that these contacts wanted the ransomware actors to disrupt health care in target countries or steal information on vaccine development. On July 16, 2020, the UK, US and Canadian governments had announced that Cozy Bear threat actors had been using “custom malware” called WellMess and WellMail to target vaccine developers in academia and the pharmaceutical industry, likely to steal vaccine formulas or other government property. The Cozy Bear actors may have received help from criminals like Conti in identifying, reconnoitering or obtaining access to these targets.

In an exchange from April 2021, Conti actor “Mango”s* government contact asked for help against “people who work against the Russian Federation.” The government’s target turned out to be the Bellingcat group of investigative journalists. As Wired magazine summarized the conversation, “Mango asks Professor whether Conti will ‘work on politics’, or if they should focus on crime and avoid ‘political fuss’. ‘Yes, we are patriots’, Professor replies, authorizing Conti’s involvement in the hack.”

This is the end of part 2a. In part 2b we explore how events surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine heightened the tension Russian ransomware hackers faced between profit-making and their duty to the Russian motherland.

*”Mango”’s real identity is Mikhail Mikhailovich Tsarev, according to a September 7 2023 US indictment. A US sanctions announcement from the same date adds, “Mikhail Tsarev was a manager with the group, overseeing human resources and finance. He was responsible for management and bookkeeping. Mikhail Tsarev is also known by the monikers Mango, Alexander Grachev, Super Misha, Ivanov Mixail, Misha Krutysha, and Nikita Andreevich Tsarev.”

Update June 2 2025: In late May 2025, The German Federal Criminal Police Office publicly identified Stern as Vitalii Nikolaevich Kovalev (also spelled Vitaly or Vitaliy Nikolayevich). US officials had unsealed a 2012 indictment of Kovalev in 2023, associating him with another Trickbot nickname, “Bentley,” that he apparently shared with fellow group member Maksim Galochkin.