When “Volt Typhoon” Blows Over: Cases of China’s Offensive Cyber Operation

Are China’s threat campaigns in preparing and pre-positioning for potential offensive activity really “a new interest”?

Last Wednesday, January 31, a press release from the United State Department of Justice stated the US government has taken down a botnet used by Volt Typhoon, a Chinese state-sponsored advanced persistent threat (APT) group targeting US critical infrastructure. In testimony before a committee of the US House of Representatives, FBI director Chris Wray warned “Chinese government hackers are busily targeting water treatment plants, the electrical grid, transportation systems and other critical infrastructure inside the US,” … “in preparation to wreak havoc and cause real-world harm to American citizens and communities…”

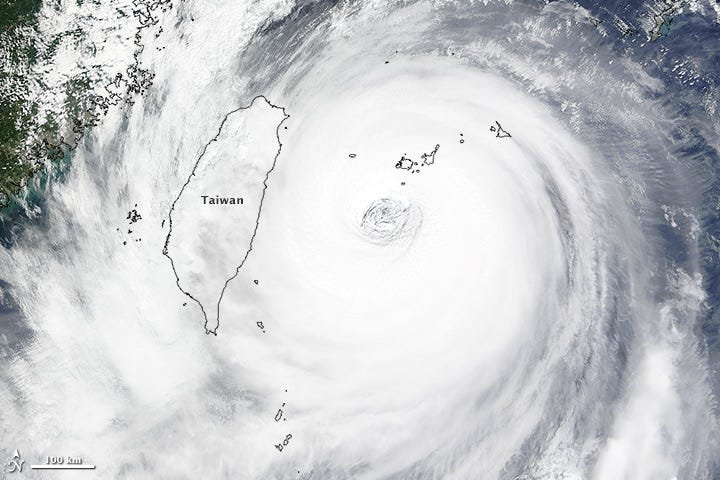

The state-backed Chinese threat group Volt Typhoon first came to public attention in May 2023 when Microsoft reported the group’s “stealthy and targeted malicious activity focused on post-compromise credential access and network system discovery aimed at critical infrastructure organizations in the US.” Microsoft assessed the “Volt Typhoon campaign is pursuing development of capabilities that could disrupt critical communications infrastructure between the United States and Asia region during future crises.” In particular, Volt Typhoon targeted critical infrastructure in communications, maritime and government sectors in the US territory of Guam, home to dozens of units of the US military Pacific Command. Following Microsoft’s report, the US National Security Agency (NSA), the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, the FBI and security agencies in Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the United Kingdom issued a joint alert warning of the hacking campaign.

In December 2023, Black Lotus Labs, the cyber threat intelligence unit of US-based network provider Lumen Technologies, identified a small office/home office (SOHO) router botnet they called KV-botnet. They also found similar routers being used to exfiltrate data from “an internet service provider, two telecommunications firms, and a U.S. territorial government entity based in Guam.” They assessed that the timing, targeting and use of SOHO devices “align with other industry reporting by Microsoft Threat Intelligence team (MSTIC), where they also observed Chinese nation-state threat actors leverage ‘SOHO devices for obfuscating their operations’.” This discovery likely led the FBI to shut down the botnet used by Volt Typhoon at the end of January 2024.

The significance of Volt Typhoon campaigns, which draw so much attention from both the private sector, the US government and foreign government partners, lies in the threat group’s likely intention to target strategically importance US assets. Furthermore, in contrast to China’s “historical focus on stealing state secrets and espionage,” meaning cyber espionage for political and economic interests, the new developments suggest a more ominous intention to prepare for destructive attacks. As US officials said, these campaigns show “a new interest in preparing and launching destructive cyberattacks against US electricity systems, water utilities, military organizations and other critical services.”

If these commentaries are correct, Chinese threat campaigns have evolved from a focus on the mere gathering information through espionage – known as computer network exploitation (CNE) – to an increased focus on preparing for offensive cyber operations such as disruptive and destructive activity. This is known as computer network attack (CNA).

Let us look into examples of Chinese cyber campaigns in addition to the Volt Typhoon case, to examine China’s “new interest” – cyber campaigns with an offensive nature.

The Definition of Offensive Cyber Operation

Private sector and government organizations have disclosed numerous cases in which APT groups from China conducted cyber espionage campaigns that benefit China’s economic development and strategic objectives. However, Chinese threat campaigns with an offensive nature seem rarer or are mixed in with cyber espionage cases. Before looking into offensive cyber campaign cases, the Natto Team would like to define a state’s offensive cyber activity, in the Chinese context, as the capability of breaching an adversary’s computer systems to carry out disruptive, destructive, or psychological effects in cyberspace to achieve strategic goals. It does not include purely cyber espionage that benefits China’s economy more broadly, except for the use of intelligence to prepare for offensive activity.

Case Examples

The following cases are based on open-source research and act as examples of cyber campaigns attributed to threat actors from China with a disruptive and destructive nature or as part of capability development or intelligence preparation for offensive activity.

1999-2000 Chinese patriotic hackers’ disruptive cyber activity: it all begins at self-proclaimed “cyberwar”

China-origin offensive activity began around the turn of the millennium, with a group of Chinese patriotic hackers showing what disruptive cyberattacks could do. In 1996, internet access became officially available to the public in China. Shortly after that, from 1999 to the early 2000s, during times of geopolitical tension, Chinese patriotic hackers waged what they termed a “cyberwar” against official websites in the United States, Japan, and Taiwan with disruptive denial-of-service (DoS) attacks or rudimentary website defacements. These state-encouraged patriotic hackers carried out their own form of offensive cyber operations to defend China against a perceived “attack”. For example:

May 1999, targeting NATO networks:

After NATO bombed the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in May 1999, the infamous Honker Union hacker group tried to “take down North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) networks” with spam emails, “an amateurish attempt at a ‘cyber blitz,’” described by a US military official.

April 2001, targeting US state and local governments:

A Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy fighter jet pilot died in a mid-air collision with a US spy plane in April that year. The Chinese patriotic hackers from the Honker Union led disruptive cyberattacks targeting hundreds of US websites, including those of the White House, the Interior Department’s National Business Center, and the California Department of Justice. The hackers accessed information on various sites and redirected site traffic to other pages. “(The attack) was more disruptive than…just about anything that we have seen,” an official from the Interior Department said at the time.

If these attempts were amateurish, the Titan Rain operation showed what state-sponsored campaigns can do.

2003 -2007 Titan Rain Operation: first publicly known Chinese state-sponsored cyber espionage activities with a military intelligence gathering focus. Was it in preparation for future crisis? Likely so

An operation that US investigators dubbed Titan Rain was the first publicly known cyber espionage campaign targeting the US that has been credibly linked to the Chinese state. It began at least in 2003 and lasted as late as 2007. First disclosed by the Washington Post in 2005, these campaigns included the following:

2003: exfiltrating national security information from Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, including nuclear weapons test and design data and stealth aircraft data;

2005: infiltrating a US Department of Defense network and targeting US defense contractors; the Army Information Systems Engineering Command; the Defense Information Systems Agency; the Naval Ocean Systems Center; and the US Army Space and Strategy Defense installation. In addition, the operation infiltrated NASA networks managed by Lockheed Martin and Boeing and exfiltrated information about the Space Shuttle Discovery program.

2007: campaigns targeting the United Kingdom’s parliament and Foreign Office, the office of the US Secretary of Defense and State Department, and Germany’s Chancellery and other ministries; some of these campaigns bore signs of possible links to the Chinese government.

Several US government cyber analysts in a 2005 Time Magazine interview confirmed that “Titan Rain is thought to rank among the most pervasive cyber espionage threats that US computer networks have ever faced.” The US government has not publicly attributed Titan Rain to China. However, Thomas Rid, professor of Strategic Studies and founding director of the Alperovitch Institute for Cybersecurity Studies at Johns Hopkins University, drawing on leaked NSA documents, attributed parts of Titan Rain to PLA unit 61398, which is also known as APT1 and was exposed in February 2013.

Furthermore, the Titan Rain operation should be seen in the context of China’s increasing preparation for offensive warfare as seen in military exercises. According to scholars, “The PLA conducted more than 100 military exercises involving some aspect of information warfare between the early 1990s and 2005 and a similar number likely occurred between 2005 and 2010.”

In July 2005, a month before the Washington Post publicly reported on the Titan Rain operation, the US Defense Department’s annual report “Military Power of the People’s Republic of China” pointed to an increasing Chinese focus on offensive network operations: "the PLA has increased the role of CNO [computer network operations] in its military exercises...Although initial training efforts focused on increasing the PLA's proficiency in defensive measures, recent exercises have incorporated offensive operations, primarily as first strikes against enemy networks."

The Titan Rain operation focused on cyber espionage, but the military intelligence gathered likely facilitated the capability development and preparation for future cyber operations that the Chinese military was also testing in its military exercises. The 2013 version of the Academy of Military Science’s book The Science of Military Strategy (战略学), the first Chinese military publication to address cyber warfare holistically, codified the importance of intelligence for offensive activity. Whether conducting defensive or offensive cyber operations, the book posited, practitioners need deep familiarity with the working principles of the network they are either defending or attacking. They need to be able to access a specific network system, discover the defects and vulnerabilities in the system, and either exploit the vulnerabilities quickly, in an offensive setting, or patch them, in a defensive setting.

2017 Equifax data breach: the new PLA Strategic Support Forces undertake intelligence preparation for future cyber operations

As part of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) reorganization, the PLA established the Strategic Support Forces (SSF) at the end of 2015. The SSF’s primary missions and functions—to provide information support, information warfare, and force development—and its organization and personnel structure suggest that the SSF plays a leading and perhaps coordinating role in the PLA’s cyber operations.

Shortly after its establishment, the SSF allegedly breached the Equifax credit reporting agency from May to July 2017. Although this cyber intrusion did not have the nature of a destructive or disruptive attack, the large volume of the data the PLA hackers obtained likely provided intelligence for future cyber operations. The US Department of Justice (DOJ) charged four members of the Chinese PLA in this case, which was only the second time that the DOJ indicted Chinese military personnel for hacking since 2014.

The indictment, unsealed February 10, 2020, states that the suspects were members of the PLA’s 54th Research Institute. These four PLA hackers allegedly obtained 145 million items of personally identifiable information (PII) of Americans, 10 million Americans’ driver’s license numbers, 200,000 credit card numbers and other PII. In addition, the PLA hackers allegedly obtained close to one million pieces of PII belonging to United Kingdom and Canadian citizens.

2020 Ransomware attack targeting entities in Taiwan: testing out destructive and disruptive tools

In May 2020, the Taiwan Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau (Investigation Bureau) reported targeted attacks on several Taiwan-based petrochemical companies and one semiconductor manufacturing plant. These attacks halted operations and forced the companies to isolate the affected networks and restore backup files. The Investigation Bureau attributed the incident to a China-based group called the “Winnti group.” Security company Trend Micro analyzed the ransomware family and indicated the attack was potentially destructive rather than merely disruptive, as “the ransomware appeared to target databases and email servers for encryption”. The German Council on Foreign Relations explained, “this particular variant of ColdLock [malware] had removed all the payment information, contact email, and the RSA public key. This indicates that no information could be provided for decryption.” If the encryption was not intended to be reversed in return for the payment of ransom, this points to a political rather than a financial motivation and implies the perpetrators were state-sponsored.

This was the first major destructive attack using ransomware by a Chinese state-sponsored group in recent years. Chinese cyberthreat actors often use Taiwan as a testing ground because of the common language. In addition, the Chinese perceive that Taiwan is rightfully part of China and that world powers will not retaliate against China for aggression against a diplomatically isolated Taiwan. (see Natto Thoughts analysis

“To Talk or Not to Talk: In US-China Communication Breakdown, Taiwan Question is the “Core of the Core” )

State actors sometimes use ransomware attacks for political reasons, to disrupt or destroy target organizations, or to clean up or cover the traces of cyber espionage. In China’s case, testing the capabilities of ransomware attacks is relatively new, but will likely continue.

So What: How Will This “New Interest” Go?

The Winnti group that deployed the ransomware attack against organizations in Taiwan in 2020 was just the beginning of China’s state cyber actors’ use of destructive and disruptive tools. Volt Typhoon, the campaign targeting critical infrastructure in Guam that has filled the headlines recently, has been active since mid-2021. It exemplifies China preparation and pre-positioning for potential destructive cyberattacks to achieve the country’s strategic objectives. Even after Microsoft’s exposure of Volt Typhoon activity in May 2023, Volt Typhoon operators did not slow down their activity. They continued expanding their botnet in August 2023 and remodeled the infrastructure of the botnet in November 2023 to target new device types, as stated in the Black Lotus Labs’ report. This indicated the Chinese threat actors’ persistence in preparing for future crises.

So, are China’s threat campaigns in preparing and pre-positioning for potential offensive activity really “a new interest,” as recent media reports say? We have to understand that China has been building its offensive cyber capability by integrating resources from the military, government, and ICT industries while making organizational changes, implementing regulations, and initiating national strategies to support the effort since at least 2000. Even campaigns such as Titan Rain and the Equifax breach, which appear purely espionage-related, can contribute to that effort. China’s quest to become a cyber superpower with offensive cyber capability is essential for China to compete as a major power in the world. We will definitely see this “new interest” continue, with more offensive cyber operations likely to come.

Further reading

The Emergence of China’s Smart State; “Chapter 8: Becoming a Cyber Superpower: China Builds Offensive Capability with Military, Government and Private Sector Forces”

PRC State-Sponsored Actors Compromise and Maintain Persistent Access to US Critical Infrastructure

Hearing Notice: The CCP Cyber Threat to the American Homeland and National Security

Secure by Design Alert: Security Design Improvements for SOHO Device Manufacturers