China’s Vulnerability Research: What’s Different Now?

China’s bug-hunting scene is maturing - more players, bigger prizes, tighter structure, and a growing focus on domestic products, driven by profit, prestige, and national security.

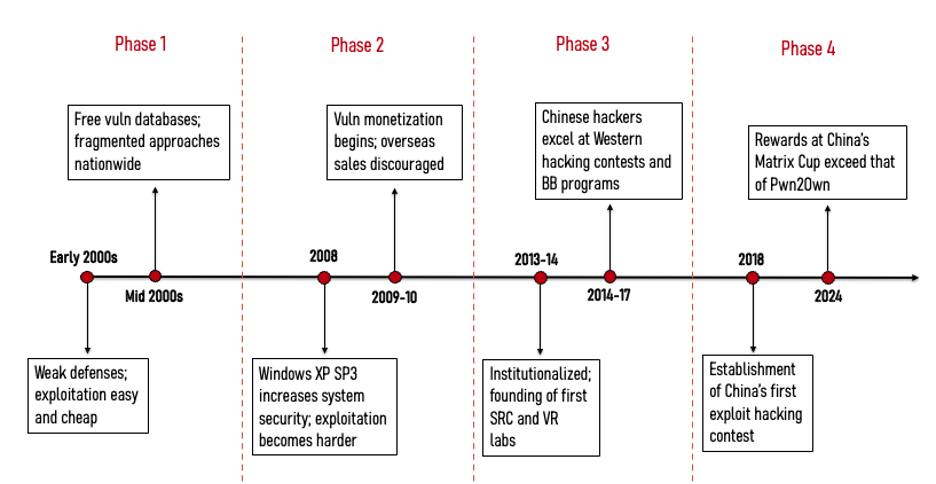

Over the past two decades, China’s vulnerability research ecosystem has undergone a dramatic transformation. In the early 2000s, it was a fragmented landscape of free databases and easily accessible, low-cost exploits. Over time, it evolved toward commercialization, with organized vulnerability markets and institutional research labs emerging within major tech and cybersecurity companies.1 By the mid-2010s, Chinese hackers were competing – and excelling – in global exploit hacking contests2 and bug bounty programs3 to identify weak spots in Western products.

As this ecosystem has evolved, the Chinese state moved to harness the vulnerability research for national priorities through both formal and informal channels. From the top down, it imposed institutional mechanisms such as direct oversight of researchers and regulations that mandate or incentivize reporting to state-run entities. From the bottom up, informal networks among prominent researchers, who exchange insights and acquisition opportunities in private forums, create parallel acquisition channels that the state can use. Together, these mechanisms form what can be thought of as China’s “vulnerability pipeline.”

In this piece, we trace how that pipeline works from the top down and the bottom up. We then highlight patterns we see emerging in the present day, drawing on over a year of Natto Thoughts research:

a more structured and diverse ecosystem,

domestic hacking contests with prize pools that surpass those their Western counterparts offer, and

a growing emphasis on finding vulnerabilities in Chinese, rather than just foreign products.

Together, these trends signal where China’s next generation of elite vulnerability researchers is headed.

Top-Down: Regulations, Rewards, and Restrictions

The state’s efforts to capture vulnerabilities began by restricting Chinese researchers from competing abroad. In 2018, the Chinese government issued rules requiring approval for researchers to compete in overseas hacking contests and mandating that vulnerabilities be reported to “public security and other relevant departments.” In practice, this became a de facto ban on Chinese researchers competing in international exploit contests.4 As China built domestic equivalents, media reports, such as MIT Technology Review, suggest that some of the vulnerabilities uncovered in these contests were passed to security agencies, such as the Ministry of State Security (MSS) and domestic-focused Ministry of Public Security (MPS) for potential operational use.

By 2021, new regulations tightened control at home. The “Regulations on the Management of Security Vulnerabilities in Network Products” (RMSV) required companies to report vulnerabilities to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) within forty-eight hours of discovery. Microsoft warned in its 2022 Digital Defense Report that “this new regulation might enable elements in the Chinese government to stockpile reported vulnerabilities toward weaponizing them.”

On paper, RMSV looks like a sweeping net that should catch everything. Yet its enforcement remains questionable, as it assumes both omniscient oversight by MIIT and uniform compliance from researchers. Neither is entirely realistic. Researchers may delay reporting, quietly trade vulnerabilities in informal markets, or simply not bother. Top-tier Chinese vulnerability researchers we spoke to admitted that they sometimes just… forget to report. Despite a landmark enforcement case in December 2021,5 enforcement likely remains uneven, underscoring the limits of regulation and the need for complementary incentives.

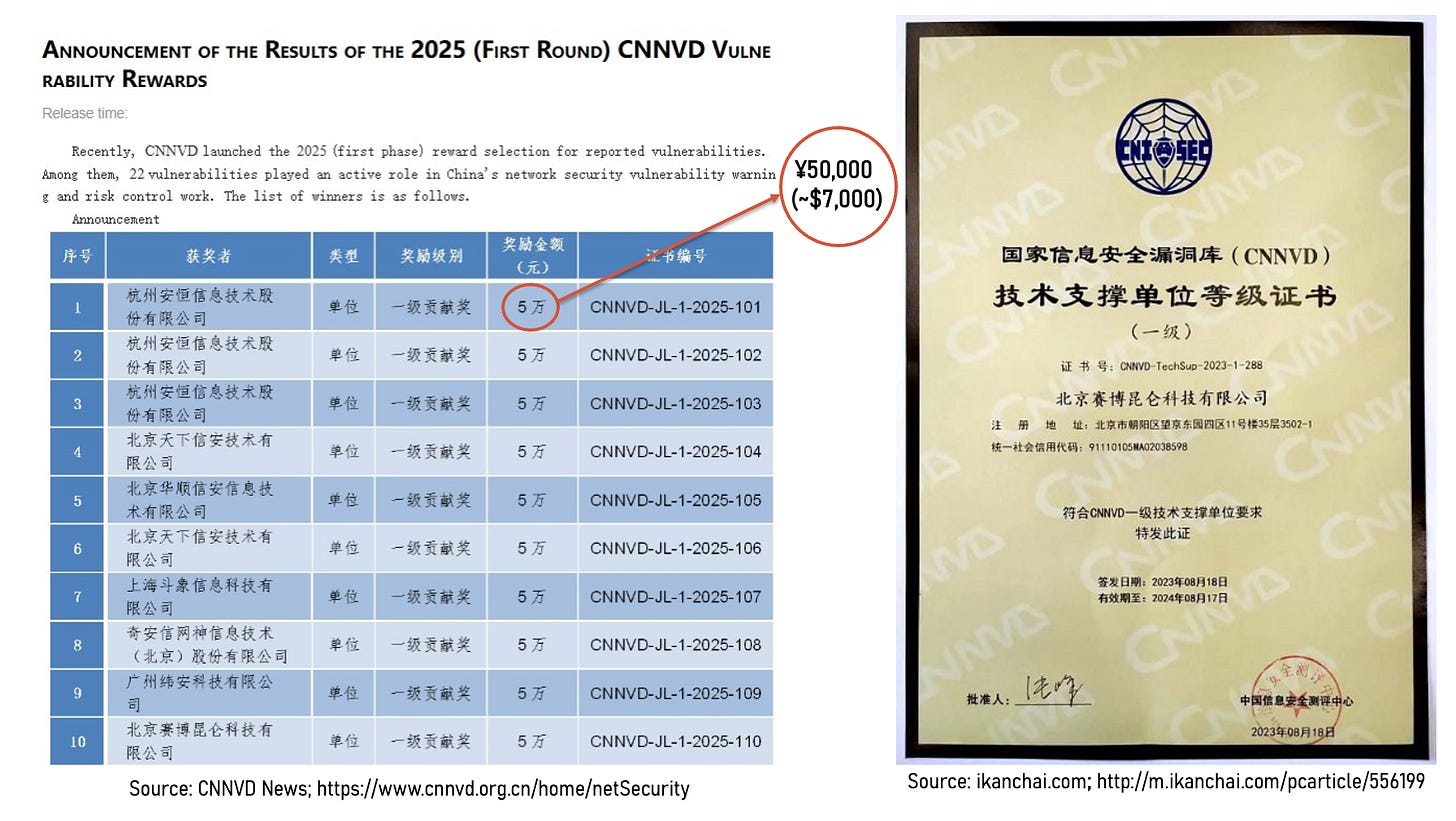

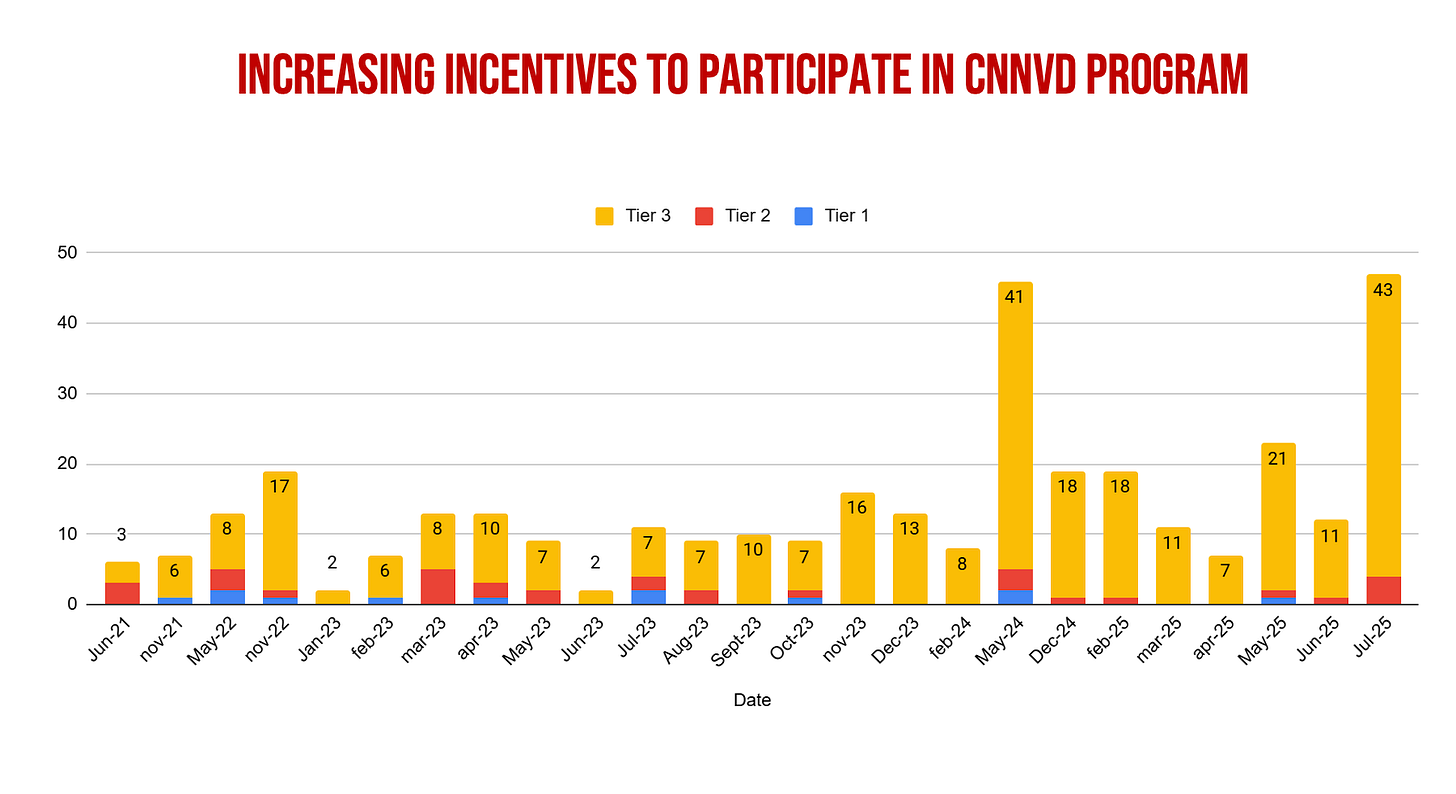

Those incentives come through the China National Vulnerability Database of Information Security (CNNVD), overseen by the MSS. Under this system, cybersecurity firms voluntarily report vulnerabilities in exchange for compensation and recognition: direct payments, certificates, and titles that boost professional standing and eligibility for government contracts. CNNVD thus complements RMSV’s legal “chill effect” by making voluntary disclosure more appealing and sustainable.

The approach works. Membership in CNNVD’s network of technical support units (TSUs)6 has grown steadily, as shown below.

In sum, the state uses overlapping mechanisms to secure vulnerabilities at minimal cost. Restrictions on foreign contests keep high-value exploits at home, RMSV enforces baseline control, and CNNVD adds incentives that turn disclosure into a source of status and income. Alongside these, various commercial actors and private markets also play an active role within China’s broader offensive cyber ecosystem, as described by Winnona DeSombre Bernsen in a 2025 Atlantic Council report and by Natto Thoughts’ co-founder Mei Danowski in her analysis of how China builds offensive capability with military, government and private sector forces published in the book “The Emergence of China’s Smart State.”

Bottom-Up: Elite Researchers & Alleged APT-linked Hackers

Alongside these institutional mechanisms, informal networks among researchers remain central to how China’s cybersecurity ecosystem functions. Two broad categories of hackers stand out, though they show up very differently. Elite vulnerability researchers are highly visible: they are top CNNVD contributors and refine their skills through hacking competitions and bug bounty programs, often focused on Western targets. This work strengthens China’s cyber capabilities, yet direct links to state-sponsored operations remain rare. APT (advanced persistent threat – usually state-linked) operators, by contrast, are largely invisible “unsung heroes,” only surfacing when exposed by groups like Intrusion Truth or through U.S. indictments.

Sichuan Silence Information Technology (四川无声信息技术) (Sichuan Silence) is a case in point. When the U.S. government exposed the company for targeting products made by the British cybersecurity firm Sophos and offered a $10 million reward for employee Guan Tianfeng, Chinese social media buzzed with questions: “Who is Guan? He’s our hero!” But nobody could find much information about him or a glorious profile of him. Instead, public records revealed a labor dispute in which Guan had sued his employer after reportedly going three months without pay. One commentator joked that Guan might as well turn himself in for the $10 million US dollar reward.

This makes us wonder: why don’t China’s elite vulnerability researchers appear more prominently in state-sponsored cyber operations? Or do they, and we just haven’t found out yet? While no direct connection to specific state offensive cyber operations, elite vulnerability researchers sometimes sit a handshake away from APT contractors.

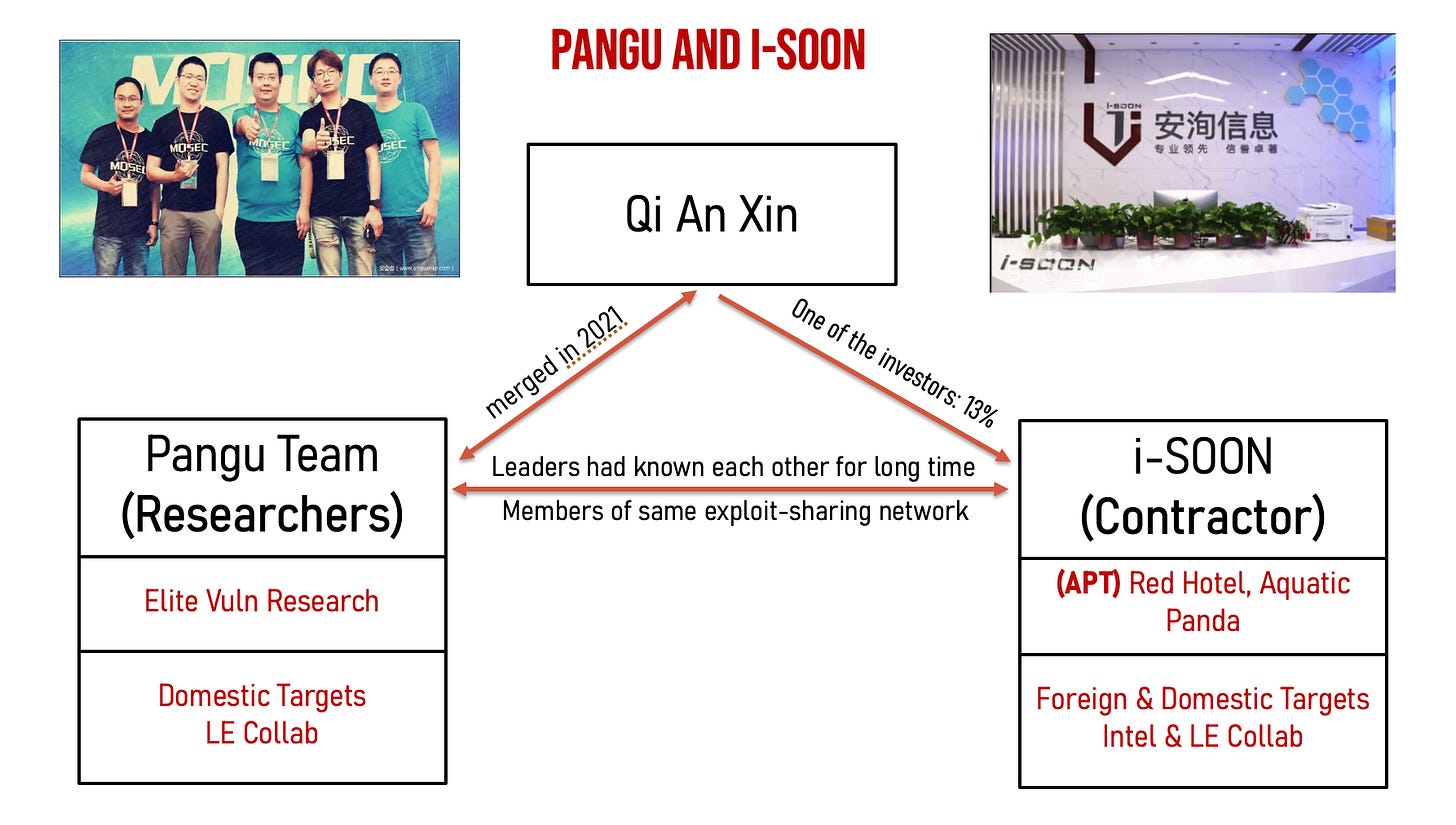

The relationship between Pangu Team (盘古团队, Pangu) and i-SOON (四川安洵信息技术有限公司), which we have examined in detail here, illustrates this dynamic. Pangu, one of China’s most prominent white hat teams, built its reputation on iOS jailbreaks - modifying the built-in limitations on the iOS operating system used in Apple products - and hacking contest wins before merging into Qi An Xin (奇安信), a major national cybersecurity company with extensive government contracts, in 2021. Qi An Xin also invested in i-SOON, a contractor linked to operations attributed to APT groups such as RedHotel/Aquatic Panda and known to work with both the MSS and MPS. Leaks from i-SOON in early 2024 revealed two key aspects of the Pangu–i-SOON relationship:

their leaders shared close ties, rooted in their backgrounds as patriotic hackers; and

Pangu showed interest in acquiring vulnerabilities and allegedly used them in compromise operations – likely in support of domestic cybercrime enforcement – within the same networks of vulnerability researchers as espionage-linked i-SOON.

Taken together, these dynamics suggest that elite researchers and APT-linked hackers do not operate in separate silos but within interconnected, overlapping networks.

Expanding the Pipeline: New Actors, Training Systems, and Domestic Priorities

In the past two years, the pipeline has widened: more actors, more structured training systems, greater investment, and an increasing focus on domestic products.

Vocational Schools: i-SOON leaks revealed in 2020 executives discussing talent recruitment from technical vocational schools in second- and third-tier cities — “we just need them to get the job done,” one explained, “and we can pay them less than those with a four-year degree.” Their instincts proved correct: two vocational schools - Qingyuan Polytechnic and Guangdong Finance and Trade Vocational College - have since joined CNNVD’s TSU list in 2023 and 2025 respectively. A third, Chengdu University of Information Technology, already has deep ties with the military, including training PLA Rocket Force cadets. For vocational schools, CNNVD membership offers prestige and better student employment outcomes, while for the state it expands the pool of vulnerability researchers at lower cost.

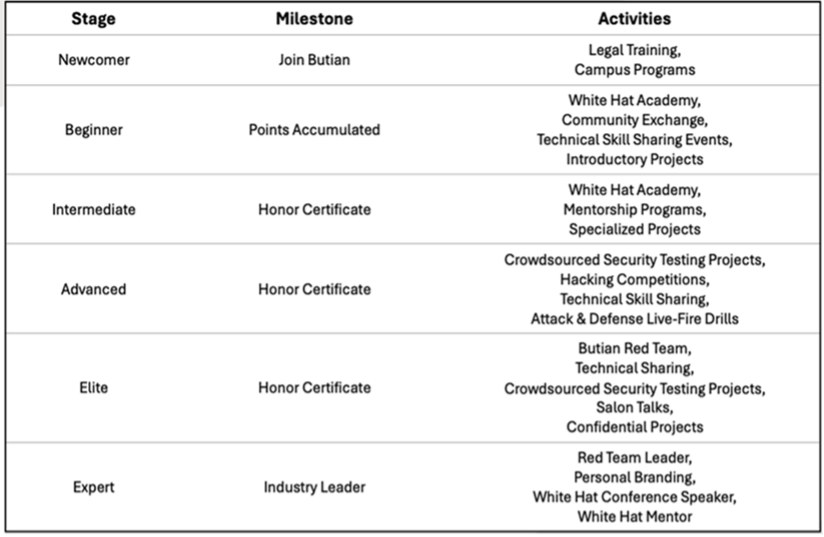

Structured Training Systems: Beyond expanding participation, major firms are now formalizing how cybersecurity talent is developed. Qi An Xin’s Butian Platform, for example, has developed a “White Hat Elite Growth System” designed to guide participants from novice to expert. The program combines theory and practice through forums, seminars, crowdsourced testing projects, and live-fire drills. Participants earn points and certificates as they progress through six phases, eventually qualifying for Butian’s competitive teams and earning honorary recognition. This model reflects how vulnerability research is being systematized into clear stages with formal milestones and rewards.

Shifting Toward Domestic Products: Contest focus has also begun to change, backed by higher prize money. From 2018 to 2022, Tianfu Cup7 participants primarily targeted Western products. Although Chinese products were added in 2021 within the same target list as international ones, their bounties were lower and attracted little interest. The 2023 edition, however, increased both the number and prize money for domestic targets.

Other contests have reinforced this trend. The 2024 Matrix Cup, for example – which we have discussed in detail here – has introduced dedicated tracks for domestic products, encouraging researchers to deepen expertise in Chinese systems. The scale of the rewards was massive: The Matrix Cup offered US$2.75 million in prizes, compared with US$1.4 million at the Tianfu Cup and US$1.1 million at Canada’s Pwn2Own in 2024. This gradual shift toward domestic products could have two main implications:

Strengthening the security of domestic products as part of the shift away from reliance on U.S. technologies – a policy colloquially known as “Delete America;”

Leveraging vulnerabilities in Chinese products for law-enforcement operations, as illustrated by the Pangu case above.

The End of Sharing?

Until recently, major contests like the Tianfu Cup featured public demonstrations of high-value zero-day exploits targeting widely used software. That transparency has now diminished. The Tianfu Cup did not take place in 2024 (or at least was not publicly announced), and at the 2024 Matrix Cup, details of discovered exploits were limited or withheld entirely. No 2025 edition of either competition has been announced. This shift raises key questions: are these events still taking place, but behind closed doors? And if so, who controls access to the vulnerabilities, and how are they being used?

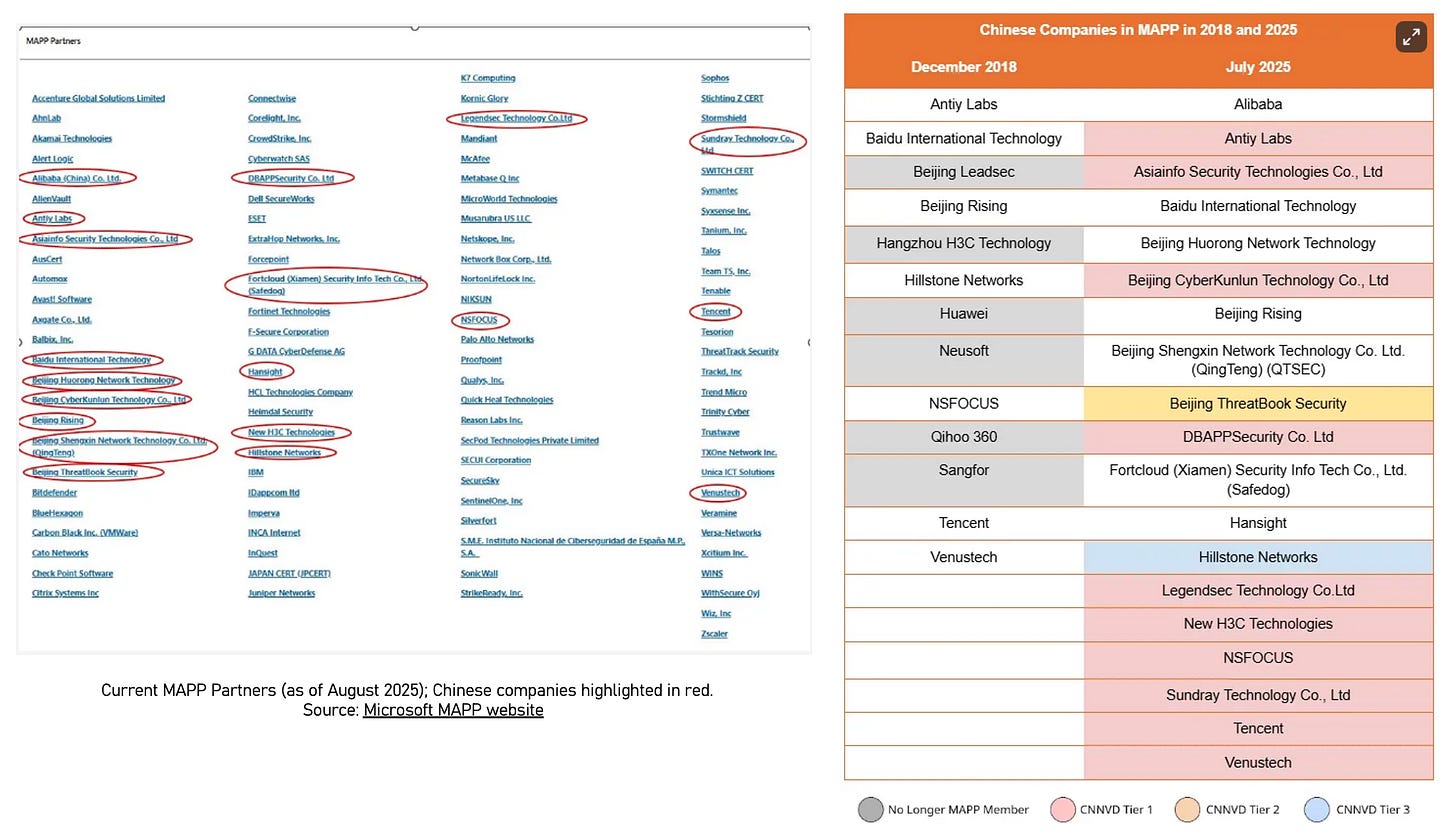

At the same time, Chinese companies with close state ties have gained privileged access to foreign vulnerability information through Microsoft’s Active Protections Program (MAPP), which provides trusted vendors with advance notice of flaws before patches are released. Out of 104 global participants, 13 are Chinese – the largest group outside the United States. These firms face conflicting pressures: bound by Microsoft’s confidentiality rules but also by domestic policies that encourage or require disclosure to the state. Suspicions persist that MAPP information has, at times, been passed to Chinese agencies and repurposed for offensive operations. In August 2025, Microsoft reportedly scaled back Chinese participation, according to a spokesperson cited by Bloomberg, though no details have been published on the MAPP website. We have examined the risks of Chinese participation in MAPP in more detail here.

Where Does Research End and Operations Begin?

Two decades ago, China’s vulnerability scene was open and improvised: a mix of hobbyists, hackers, and small collectives trading exploits online. Today, it’s structured, competitive, and increasingly state-aligned. What started as a scene of self-taught hackers chasing prestige and bounties now runs through regulated reporting systems and state-linked platforms designed to keep valuable bugs (and talent) at home.

Vocational schools feed new entrants, platforms like Butian formalize career paths, and contests are starting to give greater attention to domestic products alongside traditional foreign targets. China’s next generation of vulnerability researchers will be better trained and more numerous, operating in a system that is increasingly professionalized yet difficult to map – one where a single discovery might travel through state channels, private markets, or foreign bounty programs before anyone knows who really owns it.

Many Chinese researchers continue to submit vulnerabilities to Western bug bounty programs, a reminder that incentives don’t always flow one way. In Sophos’s Pacific Rim investigation, several submissions traced to China arrived just before attackers from the same region exploited a different flaw in the same product line. Maybe coincidence. Maybe Chinese researchers had explored a particular software ecosystem, publicly announced some of the vulnerabilities they found in order to gain recognition and rewards, but held back other vulnerabilities in the same systems for the state’s offensive use. Either way, it shows how opaque China’s vulnerability pipeline remains, and how, even in a tightly managed system, researchers still find room doing research for personal enrichment and notoriety as well as so-called “national security.”

Because publicly available data on vulnerability research trends in the late 1990s and early 2000s is limited, this analysis draws on insights shared directly by the Grugq – a prominent independent researcher – as well as by Charles Li and Zha0 of the Taiwan-based threat intelligence firm TeamT5, provided for the Before Vegas report published by the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich (2025).

Hacking competitions are events that incentivize participants to analyze the newest types of security threats, figure out how to assess them, and practice how to remediate such issues. In the otherwise discreet realm of cybersecurity, participation in hacking competitions is a practical way to publicly showcase computer skills on a national or global stage. Within this space, exploit hacking contests stand out: they focus specifically on discovering and exploiting previously unknown vulnerabilities in widely used software and hardware.

A bug bounty program is an initiative in which an organization offers monetary rewards (bounties) to independent security researchers or ethical hackers who responsibly disclose and report vulnerabilities or bugs in their software, applications, or systems.

Exploit competitions are cybersecurity contests that specifically focus on identifying, developing, and demonstrating exploits for previously unknown or unpatched vulnerabilities in real-world computer systems, software, or hardware. Unlike capture-the-flag (CTF) games that may use simulated environments, exploit competitions center on live targets.

In November 2021, security engineer Chen Zhaojun from the Alibaba Cloud Security Team discovered Log4Shell, a critical vulnerability in Apache Log4j, a Java-based logging library used by millions globally. Zhaojun reported Log4Shell directly to Apache, which disclosed it a few weeks later with a patch available. Upon disclosure, Mandiant described it as “one of the most pervasive security vulnerabilities that organizations have had to deal with over the past decade.”

TSUs are ranked into three tiers according to the number and severity of vulnerabilities submitted annually, with Tier 1 firms required to submit at least 20 vulnerabilities a year, including three rated “critical risk,” with descending requirements for Tiers 2 and 3.

The Tianfu Cup is China’s premier international-style exploit hacking contest, established in 2018 after Chinese participation in overseas competitions such as Pwn2Own was effectively banned. Modeled on Pwn2Own, it brings together top domestic security researchers to demonstrate zero-day exploits against widely used software and hardware.